What They Saw

Interview with Russet Lederman

Transcription

Hello! My name is Russet Lederman, I come from New York and I am the co-founder of a nonprofit organization called 10x10 Photobooks. Our organization has a mission to support photobooks, and the appreciation and the gaining of information about photobooks and their role within the larger photography community.

I'm here in Madrid because we curated, in collaboration with the Library and Documentation Center at the Museo Reina Sofia, an exhibition called What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999.

And this exhibition came about in 2021. It was actually the follow up of an earlier exhibition we did and publication called How We See, which had focused on contemporary photobooks by women from 2000 to 2018. And when that exhibition was touring — and it went to the New York Public Library where it started, but it was also at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, and Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris—, people started to ask us, what about the history before 2000? What were women doing in photobooks then? Because there was not a history of this sort. And there have been anthologies that have documented as well as exhibitions. In fact, one of the earliest exhibitions of photobooks was here at the Reina Sofia Museum, curated by a man named Horacio Fernández.

In looking at these past exhibitions and photobooks, we started to do statistics to see how many women were in these exhibitions, and the number we came up with was just over 10%. And so it was quite shocking to us. So as we were doing this research to do the history, we thought: "Okay, we do this history, especially since the very first book created was by a woman in 1843."

She was a botanist, a scientist, and she wanted to illustrate the algae specimens she was documenting. So she used a very early camera’s process called cyanotype, in order to document this. And in doing so, she created these small booklets and she distributed them and shared them with friends and colleagues. And so this is the very first photobook ever by a man, woman, anyone. And oftentimes, it was not noted in history as being the first photobook and rather the honor was given to Henry Fox Talbot, a man, because they said it was not produced commercially, it was distributed only with colleagues and friends.

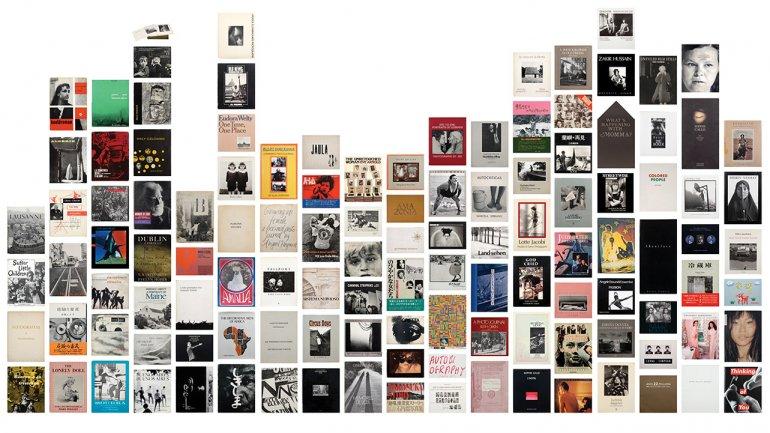

So we realized in doing this research on this history, we had to also be a little bit broader in how we defined a photobook. Being photobook not just a bound commercial book that you bought in a bookshop, but also could be a book that was an album, could be a pamphlet, could be something that was photography in print — it was bound or not bound—, a portfolio as well… And so this opened the doors for us in our research from 1843, starting with Anna Atkins, this botanist, moving all the way to 1999 with Barbara Kruger, who is an American conceptual artist, in between to find books from Cameroon, from Taiwan, from Spain, from all over Europe, Eastern Europe, within Scandinavia, within Australia, South Africa, all over the world. And in the end, we put together in the publication 247 books by women.

Of course, there are many left out. We continue to find all the time. People come to us and say, "Oh, but you didn't include this book". And this is true and we're very well aware of this. And we see this publication and reading them not just as a finite, definitive statement on what women have done in photography publishing, but we see it as the first step, opening the door a little bit so others and researchers can do work to discover all of these books that are out there. And in doing so, we hope in the future that we no longer have to do an exhibition that's just women in order to kind of say: "Oh, look, we're shining a light on this." But the goal is that we shine the light now so that 15 years from now, 20 years from now, it's an exhibition about photography books in general, and there are 50% women and there are 50% men. And this is just normal and natural. And our research and the research of scholars to come has pushed it to the point that we don't have to think about this anymore. It's not an issue. It's not something we isolate. But we are not there yet.

So we have this exhibition. It's been travelling. Like our other exhibitions our institutional partner is The New York Public Library. And so it started there. It went also to Amsterdam, where we had it in two parts: the rare books were at the Rijksmuseum —we did a special tour because the books could not be touched—, but then we had books that could be touched at a design gallery exhibition space called Enter Enter. So it was in the two parts in Amsterdam, and then it went to Boston, to the Boston Atheneum, which is one of the big old private libraries in Boston. And now it's here and it will end up going to Los Angeles as its final stop.

And so what I hope in this exhibition is that people come in and discover books that they didn't know about, whether it be a kind of more political manifesto book by The Guerrilla Girls, which is an activist group in the United States, who specifically created posters and books and public manifestations to bring to light the lack of women in museums in general or they discover a book by Angèle Etoundi Essamba who is a Cameroonian artist who did a book called Passion, which was on basically the body, the spirit of Black women from Cameroon. And so the idea is that we introduce things. And the point is so that this history is not purely Western, that this history is not purely men, that this history has a broad scope to it; and that is the goal for this exhibition.

So I hope that the people visiting come with questions, they leave with questions as well, and they discover women's role in publishing because it was often obscured. Women would either a) there were many obstacles, didn't have the money, didn't have the connections, were told that it wouldn't be of interest to anyone, and so they publish books often independently.

Or b) if they were lucky, they were working for magazines and so they were on track or they were working for a publisher. But often what we found was that women collaborated often with men. And when these collaborations happened, the men were given the credit. And so their name appears on everything, and the women were forgotten.

And so there are examples within our publication in a section we call The timeline, because this takes the kind of areas of history of this photobook publishing that can't be 100% validated, such as we found albums in Japan in the 1840s, and they were credited to the man who was part of a husband-wife team, and the wife, Ryū Shima, who ran the photographic studio with her husband, was an equal partner, her name appears nowhere on these albums. So we were not sure could we put them as a full entry. And we thought: "Okay, we make this timeline section". So it opens the door to all these events which either are kept to be 100% validated yet or contributed in some way, but a book was not produced. And so things like this and these albums, these two albums in Japan or, for example, there was a woman in Iran during the court of Qatar and the royalty in Iran at that time was very interested in photography. So they brought photography to Iran in the 1860s, and many of the women who were involved with the court learned. And so this woman was taking photographs and particularly women taking photographs of other women because of religious laws that made it more difficult or awkward for a man to take a photograph of a woman. And there she was, this woman was keeping the diary of her husband and she was taking photographs. And apparently she was putting the photographs in her husband's diary. But we could not find any documentation. We were told there was a book, an album in a library in Iran, but it was quite difficult. I contacted a friend who's a gallerist who has a gallery in Tehran, and she's like: "I don't think we can gain access to see this." So these are the things that are the questions where either through our grants or through further researchers, we hope to reveal and we hope that our project inspires.

In order to do the research and to discover many of the books that are in this project, what we did was reach out to colleagues in libraries and in academic institutions all over the world. So we reached out, obviously, to experts on South Africa or an expert who might be involved with South Asia. And we asked them: "Please, recommend books for us."

The interesting was I reached out to a historian in the U.S. who specialized in photography from Africa. And she said to me: "Well, your frame is wrong. You're looking for books that are traditional books that are bound and distributed by commercial publishers. You need to open up the idea of what is a book in order to be able to find different types of albums or different types of pamphlets or, you know, personal books that were done by artists or even those who don't consider themselves a creative individual. Because the idea of keeping an album was very much like scrapbooks, and albums was a women's job historically, and so women kept the albums for families."

So we have, for example, some albums that are not by women who consider themselves photographers or artists, but were kept and are incredible documents of a community. For example, one is an album by a woman who was living in Upstate New York, who was a well-to-do African American woman. And so it shows at the beginning of the 20th century, the life of a middle class to upper middle class black family in the Northeast coast of the United States: her family, her friends…, and many of them are cards to visit, photographs that were taken by others that were inserted into this album.

Distribution of books, and photography books in general, is not very easy, it's a very specific kind of publishing. Of course, there are publishers who focus on this. There are some very interesting ones, for example, of women in the 1860s who started their own publishing. In Germany there was a woman named Laura Bette who actually had a publishing printing business. And so she printed the books of others and she distributed them. That was highly unusual.

Most of the time, either women created, as I said earlier, these self-published projects —whether it be albums or pamphlets—, or they had associations as photojournalists with magazines, the picture press, particularly around World War Two. It was a time where women gained entry into the field of printed photography, photography and print. And so you have people like Margaret Bourke-White in the United States who was on the front lines. I mean, she was one of the few women photographing in on the front lines during World War Two. She was photographing for Fortune magazine, for Life magazine… And so she had access. So she published many books and she had the connections.

You have other people like Germaine Krull, who was here in Europe, who is a little bit of many nationalities: Dutch, German, British…, because she had to travel, obviously, around during World War Two. But she was within the artistic community and so she had access —because of her connections within the artistic community— to create more fine art type publications. She made a quite incredible book that's on display here called Métal, which is a book from —I believe, if I remember correctly— 1928, and she was responding to the kind of modernism that was taking over Europe at the point: the industrialization, the building of the Eiffel Tower, the industrial structures in the port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands. And so the book is very abstract. It's her photographs. She's shooting from angles from underneath so you see the beams of the metal. They're completely abstract in their visual patterns. So she could publish this in a fine art way because of her connections within the art world. But these books were done in limited editions.

You also had in Japan, interestingly, women who oftentimes like Eiko Yamazawa, in the 1960s, who had traveled abroad, had traveled in her case to San Francisco, studied at the Institute of Art in San Francisco, had then worked as a studio assistant with Consuelo Kanaga, who was a well-known woman photographer on the West Coast and then returned to Japan to create a school and to work also commercially in photography. And she published books and she published them kind of through a hybrid of self-publishing, also mainstream publishers. But she was one of the few. There was another one named Toyoko Tokiwa, who in 1957 published a book, and it was on working women in Japan. And working women included everyone: from nurses to women wrestlers, to prostitutes, to shop clerks. And this was something quite radical in Japan, but it was sensational, it was kind of embraced by the press as this anomaly. And she had had an exhibition of it, and so as a result of the exhibition, a publication was offered to her by a mainstream publisher in Japan.

So there is not one story.

But I think one of the things that's interesting now is the whole movement of self-publishing, because we have access digitally, in InDesign and all the tools that exist, we no longer have to wait for a mainstream publisher to come knocking at the door to say: "Do you want to publish a book?"; and some of the most interesting books being done now are being done by independent publishers.

Russet Lederman, alongside Olga Yatskevich, is the curator of the exhibition What They Saw. Historical Photobooks by Women 1843–1999 displayed in the Museo Reina Sofía in the Library’s Space D and Documentation Centre. The show, aligned with the same-titled book published by 10×10 Photobooks in 2021, assembles, within a broad frame of reference, works by women around the publication, archive and/or collection of images and photos. On display, therefore, are bound volumes, portfolios, albums, fanzines and other formats, all of which come together under the term photobook.

This initiative looks to bring into relief the role of gender in the history of the photobook, which is why it begins with the famous copy of Anna Atkins’s cyanotypes displayed in the Museo. What They Saw continues the work carried out previously in the book How We See: Photobooks by Women (10×10 Photobooks, 2018), in which female authors compiled photobooks made by women. One of the main goals of the project, explains Lederman in this podcast, is to thus expand the gaze on the history of the photobook in such a way that new narratives and research arise that are mindful of women’s role.

What They Saw: Historical Photobooks by Women, 1843–1999 (New York, 10x10 Photobooks, 2021), image cover. Graphic design: Ayumi Higuchi. Photograph: Jeff Gutterman

Share

- Date:

- 12/04/2024

- Production:

- María Andueza

- License:

- Creative Commons by-nc-sa 4.0