Desert Ambulance

Ramón Sender and the San Francisco Tape Music Center

Transcription

Desert ambulance. Ramón Sender and the San Francisco Tape Music Center.

1. A Death in Zamora

- Audio: Moritz Rosenthal. Prelude for piano, Op. 28: no. 13 in F sharp major, APR (1937/2012)

On 13 December 1981 an appeal was published in the letters to the editor section of the newspaper El País. It began as follows:

"I am the son of Ramón J. Sender and Amparo Barayón de Sender, who was imprisoned in Zamora and murdered by fascists in November 1936. I am in the middle of writing a book to commemorate my mother and would like to invite anyone that knew her, either as a child or an adult, to send me any memories they may have”. (Ramón Sender Barayón. An appeal from Sender’s son. El País, 13 December 1981)

These few lines were signed off by Ramón Sender Barayón, born in Madrid in 1934, and the same person who, three decades later, would be among those responsible for turning America’s West Coast into the setting of one of the landmark episodes in the history of experimental music in the second half of the twentieth century. Sender would, with Morton Subotnick, create the San Francisco Tape Music Center, a short-lived institution to which names such as Pauline Oliveros, Don Buchla, William Maginnis and Anthony Martin were linked.

Yet despite a belated resurgence in English-speaking circles, the figure of Ramón Sender remains obscure in his country of birth. As a result, this podcast, Desert Ambulance, seeks to break the silence surrounding his name through his own testimony, his music, and the music of some of his colleagues at the San Francisco Tape Music Center in the early to mid-1960s, the time frame of this short but pivotal collective endeavour.

- Audio: Ramón Sender. Worldfood XII, Locust (1965/2004)

To understand how Ramón became immersed in the San Francisco counterculture of psychedelia, commune life, oriental spirituality and multimedia creation, however, we must go back to 1939. Sender was one of around 300,000 Spaniards forced to seek exile in the aftermath of the Civil War, and would do so in the company of his sister, Andrea, and his father, the acclaimed author of works such as Mr. Witt Among the Rebels and Requiem for a Spanish Peasant. The Sender Barayón family docked in New York in March 1939, setting foot on the American continent, their new home. The children were taken in as refugees by Julia Davis, who would become their foster mother as Ramón J. Sender spent a number of years in Mexico before settling in the USA permanently.

Ramón Sender: My father would never talk about my mother. He may have talked a little bit to my sister about it at one point. I had trouble communicating with him because his English was very bad and my Spanish did not exist. There was one moment when we were in a bar together in Los Angeles, on a trip I took down there and we had a drink at the bar and I asked him "what really happened to my mother?" And he started talking, he was talking and he got very emotional as he went talking. Between the noise in the bar, his broken Spanish, my lack of Spanish I could not understand a word he said. I'm standing there like an idiot, with him telling me probably everything I wanted to know and I unable to understanding him. It was one my most frustrating moments.

- Audio: Ramón Sender. Worldfood VII, Locust (1965/2004)

It is fair to say that the relationship between the writer and his children was distant, caused by Sender senior’s inability to talk about the circumstances surrounding the death of his wife — so much so that he was, ultimately, against the idea of his eldest son writing a book about her. But these attempts were in vain and A Death in Zamora was published in 1989 and translated into Spanish the following year as Muerte en Zamora. In the book, there are a number of hypotheses on the reason behind this silence, although everything suggests that Ramón J. Sender’s remorse stems from him urging Amparo to seek refuge in Zamora at the start of the Civil War while he joined the Republican ranks. She would be executed in Zamora, her home town, and the same fate befell her brothers Saturnino and Antonio, both affiliated with the Popular Front.

The research that forms the basis of A Death in Zamora did not take place until after Sender senior’s death in 1982. Shortly afterwards, Ramón junior decided to travel to Spain with his wife, Judith, who would be his interpreter, in search of testimonies that would help him grasp what had forced him to be “exiled for a lifetime from even a single remembrance of (…) [his] own mother” (Ramón Sender Barayón. A Death in Zamora. Calm Unity Press, 2003, p. 17). The journey, as the ensuing book would verify, was enlightening, despite the silence that prevailed at the beginning. An example of this were the first replies he received from an appeal for help in the newspaper El País, where a reader who claimed to have known Amparo while she was alive suggested he keep the same “thick veil of silence” as his father, arguing:

“The best thing you can do at this time is to heed such a desire; let it unfold along the slow and passionate path of history, which, over time, will ultimately resolve the complex, complicated and compromised tangle of a time which, until recently, was not wise to clarify. (Román de la Higuera Alonso. Replying to Sender’s son. El País, 3 March 1982)

Although these words may seem disconcerting, one mustn’t forget that Ramón Sender learned on his return to Spain that some of his mother’s executioners were people close to her, such as a member of her family in-law and even a rejected admirer. Yet, as historian Paloma Aguilar highlighted, the early 1980s in Spain were marked by the idea of avoiding a repetition of conflict, “looking towards the future and concentrating efforts on stabilising democracy and on inclusion in Europe”. (Paloma Aguilar Fernández. Políticas de la memoria y memorias de la política. Alianza Editorial, 2008, p. 34)

Ramón Sender: What my father used to say was "I can forgive but I cannot forget." And I think that's probably the attitude I also have had and I think many others too...

2. Sonics and the Origins of the San Francisco Tape Music Center

- Audio: Allen Ginsberg. Howl, Fremeaux & Associés (1959/2016)

We just heard the voice of Allen Ginsberg reciting Howl, a Beat Generation poem first read publicly in San Francisco’s Six Gallery in 1955. At that time, San Francisco was a culturally vibrant city which, as the 1950s made way for the 1960s, went from welcoming Beat writers from New York to doing the same with their direct successors, the proponents of counterculture and the hippie movement.

Ramón Sender arrived in the city in 1957, the same year Ginsberg was embroiled in legal proceedings filed against him for obscenity, stemming from the above-mentioned poem, which would eventually seal his passage into literary immortality. Sender was a young music student who had escaped New York’s cliquey art circles, drawn to the promise of freedom in San Francisco. A few years later, he would decide to move there to continue his university studies.

In some ways, Ramón trod in the footsteps of his mother Amparo as a piano player. As a teenager, he studied under the tutelage of George Copeland, a specialist in Debussy – practically unheard of in the USA at that time – and he had also gone to Europe for a study programme he complemented with classes by such luminaries as Elliot Carter and Henry Cowell. Yet when Ramón discovered electronic music his aspirations for a career as a pianist faded.

- Audio: Karlheinz Stockhausen. Gesang der jünglinge, LTM (1956/2013)

Ramón Sender: My first exposure to electronic music was a concert in New York in 1956 put on by the league of composers and on the concert was Stockhausen's just completed piece Gesang der jünglinge and also on the concert were Louie and Bebe Barron, who had done the first electronic score for a feature film called Forbidden Planet. The Stockhausen's piece Gesang der jünglinge just knocked me out, I was just absolutely amazed by that piece of music. And also I enjoyed the lecture and demonstration by the Barrons and I would say the Barrons and Stockhausen are responsible for my getting involved. The minute the concert was over I went out and rented a wire recorder. They actually recorded on a thin wire and I could rent one of those; I rented one and started fooling around.

- Audio: Pauline Oliveros. Time Perspectives, Important records (1961/2012)

Once he had settled in San Francisco, Sender enrolled at the local conservatory, signing up for classes conducted Robert Erickson, a composer who was teaching at the institution and who would became something of a mentor for a large number of his students. His classes focused as much on improvisation as the possibilities of experimenting with manipulation and the collage of sound recordings on magnetic tape. Two approaches to music-making which, despite the disparity, would become a constant in the creations of artists linked to the future San Francisco Tape Music Center.

Ramón Sender: What I liked about tape music is it gave the composer the same freedom as the painter. He could put a stroke on canvas, in this case, it would be a sound on tape and then sit back and immediately hear it. He didn't have to go rushing down the hall and grab the cello teacher and say "please, please, try this part" and see if it works, which was the way I used to. Even when I was a student there I would write a part for an instrument and I grabbed the teacher and had it tried out. In this case I didn't need an intermediary, I could hear the sound on the tape and decide if I liked or not, it was a wonderful freeing. It freed me from those dots on paper that I've been making for so many years. It freed me from the attitude of the performer who I would have to convince to play it. So many times they were not interested in playing my music. So anyway, that is why, how I got into it as a classical trained composer, and I should say overly trained because I started very early studying with various people and I don't think it did me any good. I think it just froze me up, I mean there was a point when I was 20 years old, I'd be sitting in front of my music manuscript, put a note down and I would say "Now, what would Stravinsky think of that note? What would Schönberg think of that note?" and by the time I decided it had slowed me down a lot. I lost any sense of spontaneity about composition by having too many teachers.

I was saved from all this by the tape recorder and also by finding a very good teacher, finally, after having studied with Elliot Carter, Henry Cowell and Harold Shapiro in Rome, at the conservatory. The man I finally found out here in California, his name was Robert Erickson, had been recommended as a very fine teacher and indeed he was. He specialized in encouraging students to improvise, so we had improvisation sessions which then turned into a group of students or ex-students meeting on their own: Pauline Oliveros, Terry Riley, Loren Rush, Phil Windsor. They are all people who either studied with Erickson still came by and visited the class or people I knew in other ways, but Pauline and I became very good friends, Terry and I also, except Terry left for Europe surely after that year and spent a number of years in Europe. So that's how things got started; I decided to invite my closest composer friends to create a new piece in this new studio at the conservatory attic and then for the first concert, of what I planned a year of concerts; I had new works by Pauline, by myself, by Terry and by Phil Windsor.

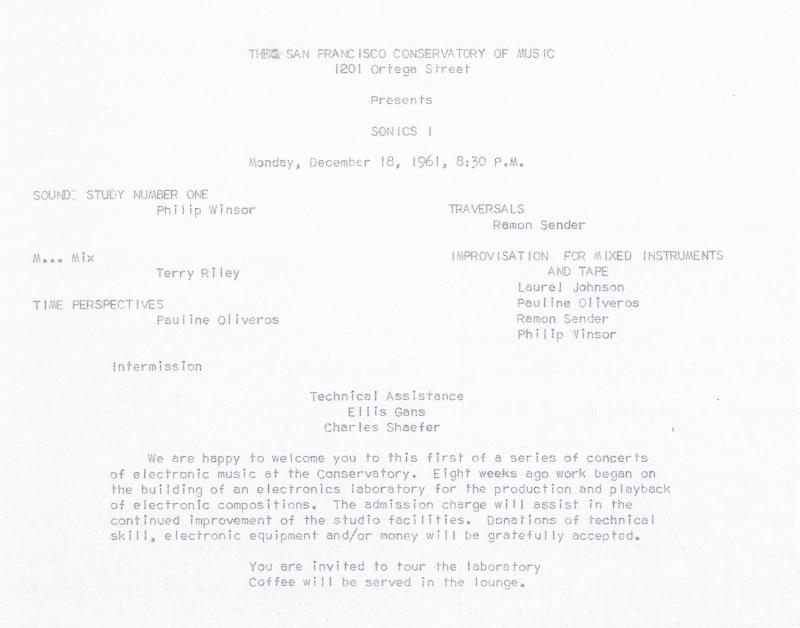

Sender’s fascination with music for magnetic tape led him, in October 1961, to assemble a basic recording studio in the conservatory attic. Despite the economy of means, the studio enabled him to produce different electroacoustic pieces, many of which first saw the light of day over the course of a seminal concert series called Sonics. Therefore, between December 1961 and the summer of 1962, the San Francisco Conservatory would welcome these sessions, its programme allowing for compositions such as Pauline Oliveros’ Time Perspectives – playing right now – which opened the series.

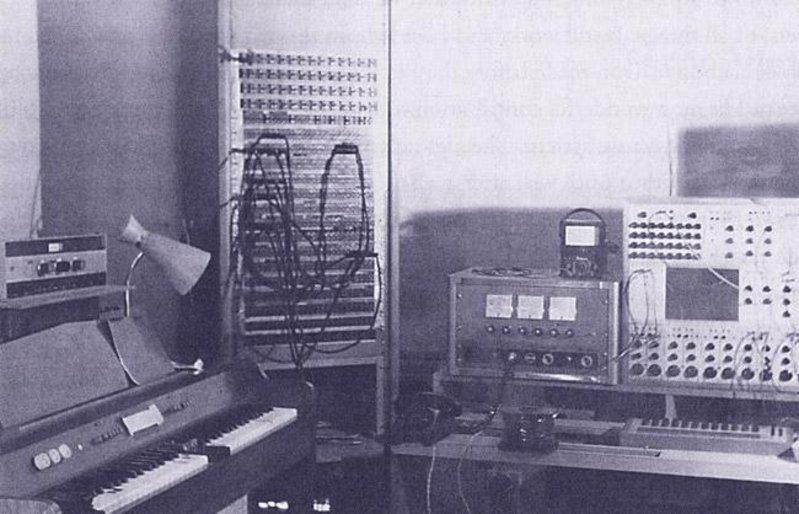

Ramón Sender: In terms of the attic studio at the conservatory I had not visited other studios and the sources of information I had were a few descriptions in books; there weren’t many books around… but mainly I just knew what I needed, as many tape recorders as I could afford and some things that made noise. So I had two or three tape recorders, one of them, two of them professional quality I would say, and then a small mixer and then I had an upright piano, just the strings and the soundboard that I could use for echoes, as I would put a microphone in one end and push the speaker up against the soundboard and then I would echo sounds through the piano and then what else did I have? I had an old bed frame, a wonderful iron bed frame that I put a magnetic microphone on it, and if I stroked it with a stick, it sounded like all the bells of Venice going off at the same time. It was a wonderful sound. I worked with what I called found sounds. Since I didn't have the technology for the fancy equipment, I turned to what was available.

- Audio: Ramón Sender. Kronos, Other Minds (1962/2016)

Another of the compositions created in the conservatory attic in San Francisco was Kronos, one of the first Sender put together from this unique sonic laboratory and first performed in the third session of Sonics, sharing the billing with pieces by Stockhausen, Mauricio Kagel and Luciano Berio, with tapes probably loaned by Berio, guest professor at the time at Mills College and someone Sender would meet through Morton Subotnick, another of the first attendees at this concert series and a future associate and collaborator.

Ramón Sender: So for my piece Kronos, the piece starts with a sort of a white noise sound; it's really me dragging a pair of scissors over an aluminium sheet that gave this kind of white noise shimmer and later in that same piece there is sort of a slowed down water sound that I recorded in the conservatory bathroom and slowed down the water. And when you slow it down enough it begins to sound like tablas, like the Indian drums, and I really like that so I added that to the piece. I was doing a lot of, “whatever I could find that interested me sounds,” so I suppose you would say we were more a musique concrète studio than we were electronic because we just didn't have the equipment.

One of the first things I did when I started the studio at the conservatory is I took some of their official letter paper with their logo and I wrote requesting donations to every major company I could think of. And of all those letters I must have sent out thirty; the only one who responded positively was Hewlett Packard who sent me two sine wave and one square wave oscillators. It was very generous. It was obviously a donation to the conservatory but it was a very generous thing for them to do and we got a lot of use out of those oscillators. In fact, in this piece Kronos I decided to use the oscillators as a performing instrument so I'm sitting there, it has a large dial on it... I tried to play melodies on it. So that piece involved that and the conservatory choral group came up to the attic and I said now "I just want you to make a lot, improvise a lot of sounds together and I'm gonna record you as a source". So they did and then I took those sounds of their voices and put them through the upright piano as a resonating echo chamber and I was able to get these bursts of vocal sounds that go "aaahhh" and fade away very slowly, "aaahhh." So those were my basic resources: the oscillator melody, the bursts of voices through the piano's strings echoing, the slowed down water and the white noise. Those were all my different sounds as I recall.

- Audio: Ramón Sender. Kore, Locust (1961/2006)

Although the Sonics concert series was a resounding success, Sender did not receive backing from the conservatory directors to fund a second season. As a result he decided to join forces and team up with Subotnick given that the latter had a modest home studio in which he had begun to experiment with magnetic tape compositions, creating scores for theatre productions. This collaboration gave rise in the summer of 1962 to the San Francisco Tape Music Center, which was based in an old Victorian house in the Russian Hill neighbourhood. A new concert series was staged in the Center and a second session, organised in November of the same year, included another of Sender’s creations, made in the studio set up in the conservatory: Kore, a piece with a similar production process to Kronos. In this instance, it was dedicated to his daughter Xaverie, with the title referencing the Greek goddess Persephone.

In the spring of 1963, the San Francisco Tape Music Center changed location, moving to 321 Divisadero Street. The move to bigger premises brought with it an invitation to share rent and workspace with other artists from the local scene, including the radio station KPFA and Ann Halprin’s dance company, in which Subotnick was musical director.

Thus, it became detached from the customary rigid academic medium, making up for a lack of resources with the promise of facilitating access to any musician wanting to make use of its facilities and ensuring that their creativity would not be inhibited, neither by the expectations of specialised circles nor the audience. That said, the freedom granted to the artist must not be confused with the defence of individualism, the opening up of the San Francisco Tape Music Center set out from a desire to be involved in the musical life of the community in such a way that it participated in transforming its cultural milieu.

Ramón Sender: I was thinking back to the days of guilds; of course we had the musicians’ union and the unions are an attempt to keep the guild concept going except in most cases musicians’ unions don't help that much. My idea was to have a group of composers and performing musicians who could be approached by anyone in the city needing someone for whatever reason. We began to do this a little bit, we traded music for plays to the biggest drama group here in the city. We said: “we'll do music for your plays in return for an introduction to your best sponsor”. So they introduced us to the woman who they felt would be friendly to some of our projects and she did help us and buy a piece of equipment and in return we did the music for three of their shows. That kind of deal was what I was hoping we would see more of. I mean... we were not a commercial studio, but every once in a while, somebody would call us up with a small job that would pay us a little something. The idea we had... we also at one point had the idea that we would not list the composers on the programs, we would list the pieces but basically the composers would be anonymous and that was a thought that came and went very quickly but it was part of, I think, the same idea, the music was important and not the personality.

3. Multimedia and Psychedelia. From Desert Ambulance to the Trips Festival

- Audio: Ramón Sender. Desert Ambulance, Locust (1964/2006)

In addition to constituting a space for electroacoustic production, the San Francisco Tape Music Center would become a place for promoting multimedia creation due to the significant onstage content of its concerts. On one side, they could rely on the presence of dancers from Ann Halprin’s company, their choreographies interweaving sculpted real-time light collages made by people like Anthony Martin, a painter who had put his brushes down to experiment with the moving image, foreshadowing the light shows at the gigs of a burgeoning psychedelic rock scene. Dance and projections that could by no means be understood as a mere visual accompaniment to musical pieces. Rather, they were a form of collaborative work from different disciplines striving for multi-sensorial and, to some extent, unpredictable pieces.

One example was a composition first performed in February 1964 called Desert Ambulance, defined at the time by critic Alfred Frankestein as a display of “aural pop art”, while its creator, Ramón Sender, described it as "a vehicle of mercy sent into the wasteland of (academic) modern music” (David Bernstein (ed.). The San Francisco Tape Music Center. 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-garde. University of California, 2008, pp. 23–24). Desert Ambulance was designed with Pauline Oliveros as a soloist; she played the accordion as an accompaniment to a piece for magnetic tape while her body became a screen upon which Anthony Martin’s images were projected.

Ramón Sender: The title Desert Ambulance came from a pile of garbage that some Christian missionary group had cleared out of their office downtown. I found these photographs, and one was titled Desert Ambulance and it showed an ambulance with a bunch of black natives in some sort of uniforms; they’re obviously ambulance people. The title stuck with me, unfortunately I lost the original photograph; I wish I still had it, I looked all over for another copy but never found it. It was years after I created the piece that I connected Desert Ambulance to the memory of my sister and I being evacuated by the French Red Cross from Zamora and I thought, well that ambulance must have impressed me as a little boy and that's why this memory trace lingers in my mind and that's how I picked the name for the piece. It's a far connection but it was one that meant something to me at the time and then, as far as how I created the piece we saw an advertisement, somebody was selling this unit called the Chamberlin in the San Francisco paper and it turned out the man was a doctor, he was an MD of a well-known San Francisco family. Morton Subotnick and I went out there and looked at the Chamberlin and we didn't know what it was and sure enough it was interesting, it had a tape player back under every key on the keyboard so when you press the key down, it was like a precursor of the Mellotron. I'm not sure if the Mellotron uses real tapes but the Chamberlin used a 3/4 inch 3-track pre-recorded tape under every key and you can select the track, and you can then have a trumpet or you can select another track and have a voice, it also had a rhythm section, you could key into that.

Both Morton and I were interested in the unit because we thought maybe we can record our own sounds into it. So, we asked him: “Can we come back and make some tapes?” So we did, we both we made tapes. And those source tapes I made there were the ones I used to create the piece Desert Ambulance for Pauline. Then I decided that the live performer, the accordionist, would make electronic sounds or voice sounds, voice duplicating electronic sounds and all the instrumental sounds would be on the tape from the Chamberlin. I wanted to do projections on the performer, the performer was dressed in a white laboratory coat. The film projector had a specially cut aperture, it was carved to be the size the person sitting there. I didn't want any projection spilled behind her and otherwise I wanted the film to be only on the person with no extra. That worked very well and then we could have the earphones on Pauline, I was telling her what notes to play. Her score was dictated to her over earphones since it was too dark for her to follow a manuscript score. So, I'm on the score, I'm saying "there's a low b flat coming, please play the b flat with it or make the following vocal sounds." So I was making vocal sounds for her to copy, that was the tape the audience was not supposed to hear obviously and they were hearing the Chamberlin's sounds and the live accordion. So that was basically it, and then Tony [Martin] did a very nice score for it which he later adjusted so that the piece could travel and be presented in other places without either he or me present. See… up until then of course we would need a live projectionist but with his special score it could be done on a video projector along with the tape, so it was basically the idea. But it turned out to be a popular piece and Pauline did [it] a number of times and then a couple of other accordionists have done it also.

- Audio: John Cage. Atlas Eclipticalis with Winter Music, Electronic Version, New World (1964/2014)

The San Francisco Tape Music Center quickly became, in under three years, one of the foremost places, and a reference point, in experimental creation, with the event known as Tudorfest one of the biggest milestones in its brief history. Between March and April of 1964, they arranged a series of concerts dedicated to David Tudor, John Cage’s preferred performer for his compositions. In point of fact, a number of Cage’s pieces were played at the festival, such as Atlas Eclipticalis, performed by an ensemble headed by Sender, at the same time as Tudor played another composition on piano: Winter Music.

Ramón Sender: This was really Pauline's project. I think she had met David Tudor. They together decided to do a week of Cage's music and other music also. I think it was a series of 3 concerts repeated twice each and we approached the radio station, KPFA: “would you be willing to live broadcast? Yes”, they were happy so they came in to do the live broadcast. Different of us [sic] took different jobs, I was invited to conduct one of the Cage's pieces. Towards the end of the week, John Cage came by, he was very nice, very open to everything, he wanted to hear all our music, what we were doing… he was very charming and then David Tudor became good friends with everyone including our technician. The Cage's thing was good for us, it made people take notice of us within the larger musical community, the more symphony-art museum crowd because The New Yorker had had a large article on John Cage that summer and suddenly he was fashionable among the fashionable crowd. In fact, the ladies’ auxiliary of the museum called us up and said: "please, would somebody come down here and talk to us about John Cage because we are going to have a concert of his”. So I went down and talked to these coiffured, well-tailored ladies about John Cage and it was okay. We were getting pretty well-known in the city, whenever a composer visited, the official welcoming committee from the city would send him to us, so we had a lot of visits from various dignitaries, which was nice. Stockhausen came by and Usachevsky from the Columbia Princeton Center came by, a whole of group of young Swedish composers came and they came on Swedish government grants to study with us and we were so impressed that a government were actually paying these young composers to come and be with us, that was so enlightening that we just couldn't believe it.

- Audio: Morton Subotnick. Silver Apples of the Moon, Wergo (1967/1997)

David Tudor was one of the first to take an interest in the major findings that rose from the heart of the San Francisco Tape Music Center: the modules that would become the 100 series of the Electric Music Box instrument, one of the first commercially available synthesisers that appeared in 1964, and subsequently known as the Buchla, named after its creator.

Don Buchla studied physics and music, and his interest in electronics prompted Sender and Subotnick to assign him the task of designing a radically new instrument that would transform approaches to music in the years to come and was popularised by Subotnick in works such as The Wild Bull and, particularly, Silver Apples of The Moon.

Ramón Sender: We put an ad in the paper looking for an engineer, which brought some pretty funny people but then Don Buchla showed up. He claims he just came to a concert, he wasn't answering an ad or anything but we immediately grabbed him. We described what we wanted and I must say that really Mort was the main designer, shall we say, for what Buchla was going to do. I sat in there and I told Morton what I wanted too but he was more interested, I was interested too but just in a more general way. I think at that point we got the drama group we were doing music for, we got their patron to give us a check and that is the way I think we got into the Buchla. Six months later Don showed up with a couple of modules and we were very excited and that was the beginning of what became the Buchla box. And Morton was the one who didn't want a keyboard, a standard keyboard, he was a clarinetist, he didn't particularly like keyboards and I don't blame him. He thought what we ended up with was a lot more flexible and I think he's right, the keyboard would have locked us into an older way of looking at things and was good not to have it and other than that the Buchla box could be used in live performance. I think Subotnick has certainly proved that the Buchla can do live performances very well. His whole career basically now is based on creating a new version of the piece every time he performs it. The machine, the Buchla, was flexible enough, so it could be used as sound source for preliminary tapes for creating a piece or could be used live in an improvisation live concert.

- Audio: Ramón Sender. Xmas me, Other Minds (1968/2016)

We just heard a recording from December 1968, one of the few records of Sender at the controls of a Buchla synth. One of the first public demonstrations of the instrument occurred a few years previously, at the Trips Festival held in January 1966. The project sought to reflect the experience of psychedelic drugs through the sensorial expansion afforded by multimedia creation, be it through the medium of music, experimental film, light shows, dance or theatre. The event was a joint initiative by Sender, Ken Kesey and Stewart Brand; Kesey was a figure with close ties to the Beat movement, and headed the band known as the Merry Pranksters, a type of commune that travelled around the USA on a bus, promulgating the liberating potential of LSD, which was legal at the time. Brand, meanwhile, would go down in history for being the author of Whole Earth Catalog, an essential guide and introduction to a way of life endorsed by counterculture. Thus the festival would become a kind of gargantuan performance in which, among others, the Merry Pranksters and Allen Ginsberg performed, as well as rock groups like the Grateful Dead and Big Brother, a band in which Janis Joplin was later the lead singer. In some respects, the Trips Festival could be viewed as a collective celebration of the most daring artistic community on the West Coast, and one of the founding acts of the hippy movement.

Ramón Sender: As time passed, I felt pretty burnt out by the concert format, I was kind of getting bored with concerts and wanted to do something different. Our friend Tony [Martin] who was doing our visual projections said "you should talk to this guy, Stewart Brand, he's doing a multimedia show called America needs Indians." So I called Stewart up and we talked and we did have a lot of interests in common. And Stewart called me a week or so later saying "Ken Kesey is in town, and Kesey is doing these acid tests. -In fact, there was one that December at the Fillmore I went to.- He wants to do a weekend, he is calling a Trips Festival which would be all the most interesting groups doing things in the city, bringing them all together, are you interested?" "Yes, I am, I don't know if the rest of my group is interested but I'll find out." So that was the beginning of collaborating on the Trips Festival which of course became a big deal. And I was playing from Kesey's idea: get together the groups during the best trips and put them all under the same roof for 3 nights. So when Stewart said: “what groups would you recommend?” I was living in Berkeley at that time, and I said "there's a theatre group here, it is quite good, doing the same thing with theatre that we were doing with sound," so I invited them: they were Ben and Rain Jacopetti and they had a group called Open Theatre and in this Open Theatre various actors or groups would perform. So they came in and the idea was each group would bring a rock band, so the Jacopettis decided to bring a Berkeley rock band called The Loading Zone. I had contact with Big Brother who had been, not directly involved with the Tape Center but indirectly involved. Later Janis Joplin came to some or our events, but Big Brother at this time did not have Janis, this was pre-Janis but I did invite them. I said "we need a band as part of our evening at the Trips festival, would you be the band?" and they said yes. So then we had Big Brother, we had Loading Zone, and of course Kesey and the Merry Pranksters came in with the Grateful Dead. I don't think Stewart brought a band, he set up a tipi in this large auditorium and he had these projections and music. The weekend was unusual and really unique and brought together groups of people who had not been in contact with each other. And suddenly everybody was looking around thinking "my god, it's not just me, it's really happening" and there was a lot of that feeling that year. We had a lot people, all of our regular people came and a lot of our friends and filmmakers we were in contact with, we called them up: Bruce Bailey, Bruce Conner, number of others they all came and projected films from the balcony as part of the show on one night and anyone who was in all connected with us showed up plus of course many, many other people. Ann Halprin came with her dancers, set up a huge cargo net; they used to pull cargo on the ships; they had it hanging from the ceiling and they were climbing, the dancers, climbing on the net. Stewart Brand brought a friend who was a professional trampoline artist and set up a big trampoline and then put a strobe light on the trampoline so he was doing these incredible gymnastics in the strobe, it was really amazing. Anyone in the art community in San Francisco who had any interest was there, I'm sure.

- Audio: Grateful Dead. It's All Over Now Baby Blue, Rhino (1966/2003)

Equally, the Trips Festival could be seen as the beginning of the end of the San Francisco Tape Music Center. Firstly, because the centre received a sizeable grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, the second inside the space of a year, which entailed an obligation to become affiliated with an academic institution — it moved to Mills College, California, in the summer of 1966. Secondly, because by then Morton Subotnick had decided to move to New York, while Ramón, after going on a desert meditation retreat, preferred to leave the scene and change tack by embracing the tribal way of life in the Morning Star and Wheeler communes, where he would remain engrossed in musical creation through other mediums and ends, at least until the turn of the 1970s. Before the founding members left, Pauline Oliveros would take on the management of the Center’s new chapter, backed by Anthony Martin and William Maginnis. The San Francisco Tape Music Center thus became the Mills Tape Music Center, concluding an episode in the life of its leading figures and making way for scores of new narratives, the echoes of which still reverberate today.

Bibliography:

Paloma Aguilar Fernández. Políticas de la memoria y memorias de la política. Alianza Editorial, 2008

David Bernstein. Music from the Tudorfest: San Francisco Tape Music Center, 1964. New World, 2014

David Bernstein (ed.). The San Francisco Tape Music Center. 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-garde. University of California, 2008

Francisco Caudet. ¿De qué hablamos cuando hablamos de literatura del exilio republicano de 1939? Arbor, vol. 185, nº 739, 2009

Francisco Caudet. El exilio republicano de 1939. Cátedra, 2005

Román de la Higuera Alonso. Contestación al hijo de Sender. El País, 3 March 1982

Ramón Sender Barayón. A Death in Zamora. Calm Unity Press, 2003

Ramón Sender Barayón. Llamada del hijo de Sender. El País, 13 December 1981

Desert Ambulance is a three-podcast series devoted to Ramón Sender Barayón (Madrid, 1934), a name at once familiar and obscure in Spain. The podcasts constitute an attempt to retrieve and shed new light on this figure by underscoring his musical contribution, particularly his work in the early to mid-1960s from the San Francisco Tape Music Center, a pioneering institution Sender would found with Morton Subotnick in 1961. Despite its short life, the Center represents one of the most interesting chapters in the history of electroacoustic music and, indeed, multimedia creation.

However, to put an approach to this artist into context, there is a need to look at Ramón’s upbringing in the USA after his family – his father was the esteemed writer from Aragón, Ramón J. Sender – was forced to flee from Spain in 1939. His mother, the pianist Amparo Barayón, would not be so lucky and lost her life to Franco’s armed forces shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War. This incident was shrouded in unusual circumstances and enveloped in a silence that Ramón would have to live with his whole life.

These three podcasts compile Sender’s testimony, courtesy of an interview, and are complemented with different records of his compositions and those by some of his contemporaries and travel companions. The frame of reference is an account developed by scholar David W. Bernstein through his research on the San Francisco Tape Music Center, from its inception to its heyday, prior to its members going their separate ways and in parallel to the emergence of counterculture and psychedelia on America’s West Coast.

Francisco Caudet claimed that post-war Spanish literature must be depicted not on purely territorial grounds, but also extraterritorial terms given the circumstances that forced thousands of Spaniards to leave the country (Francisco Caudet. ¿De qué hablamos cuando hablamos de literatura del exilio republicano de 1939?, Arbor, vol. 185, no. 739, 2009). Thus, Desert Ambulance seeks to follow suit with a composer whose work is irrevocably linked to an episode that would truncate the trajectory of the twentieth century in Spain.

Group photo. San Francisco Tape Music Center. From left to right: Tony Martin, William Maginnis, Ramón Sender, Morton Subotnick and Pauline Oliveros

Sonics Programme. December 18, 1961

Study of the San Francisco Tape Music Center with the first Buchla system on the right (late 1965, early 1966). From left: Chamberlin Music Master, Patch Bay, auxiliary amps and the Buchla box. Photograph by William Maginnis

Share

- Date:

- 04/03/2020

- Production:

- Rubén Coll

- Voice-over:

- Madeline Robinson

- Acknowledgements:

Ramón Sender Barayón, José María Llanos, José Manuel Costa, Javi Álvarez and Luis Olano

- License:

- Produce © Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (con contenidos musicales licenciados por SGAE)

Audio quotes

- Moritz Rosenthal. Prelude for piano, Op. 28: no 13 in F sharp major, APR (1937/2012)

- Ramón Sender. Worldfood XII, Locust (1965/2004)

- Ramón Sender. Worldfood VII, Locust (1965/2004)

- Allen Ginsberg. Howl, Fremeaux & Associés (1959/2016)

- Karlheinz Stockhausen. Gesang der junglinge, LTM (1956/2013)

- Pauline Oliveros. Time Perspectives, Important records (1961/2012)

- Ramón Sender. Kronos, Other Minds (1962/2016)

- Ramón Sender. Kore, Locust (1961/2006)

- Ramón Sender. Desert Ambulance, Locust (1964/2006)

- John Cage. Atlas Eclipticalis with Winter Music, Electronic Version, New World (1964/2014)

- Morton Subotnick. Silver apples of the moon, Wergo (1967/1997)

- Ramón Sender. Xmas me, Other Minds (1968/2016)

- Grateful Dead. It's all over now baby blue, Rhino (1966/2003)