Ambulancia en el desierto

Ramón Sender y el San Francisco Tape Music Center

Transcripción

Ambulancia en el desierto. Ramón Sender y el San Francisco Tape Music Center.

1. Muerte en Zamora

- Audio: Moritz Rosenthal. Prelude for piano, Op. 28: no 13 in F sharp major, APR (1937/2012)

El 13 de diciembre de 1981 se publicaba en la sección de cartas al director del diario El País un llamamiento que arrancaba de la siguiente manera:

"Soy hijo de Ramón J. Sender y de Amparo Barayón de Sender, quien fue encarcelada en Zamora y asesinada por los fascistas en noviembre de 1936. Estoy en medio de escribir un libro conmemorativo acerca de mi madre, y quisiera invitar a alguien que la conociese, sea de niña o de adulta, para enviarme sus recuerdos." (Ramón Sender Barayón. Llamada del hijo de Sender. El País, 13 de diciembre de 1981)

El firmante de esas líneas era Ramón Sender Barayón, nacido en Madrid en 1934, el mismo que tres décadas después sería uno de los responsables de convertir la Costa Oeste norteamericana en el escenario de uno de los episodios más decisivos en la historia de la música experimental de la segunda mitad del siglo XX. El motivo, su participación en la creación, junto a Morton Subotnick, del San Francisco Tape Music Center. Una institución de breve existencia a la que estuvieron vinculados nombres como los de Pauline Oliveros, Don Buchla, William Maginnis o Anthony Martin.

Sin embargo, la figura de Ramón Sender si bien ha sido objeto de una tardía recuperación en el ámbito anglosajón resulta prácticamente desconocida en su país de nacimiento. Por eso esta capsula, Ambulancia en el desierto, pretende romper el silencio existente en torno a él a través de su propio testimonio, su música y la de algunos de sus compañeros del San Francisco Tape Music Center durante la primera mitad de los 60s, el tiempo que duró esta corta pero crucial aventura colectiva.

- Audio: Ramón Sender. Worldfood XII, Locust (1965/2004)

Pero para entender cómo Ramón recala en el San Francisco contracultural de la psicodelia, la vida comunal, la espiritualidad oriental y la creación multimedia hay que remontarse a 1939. Ya que Sender fue uno de los casi 300.000 españoles que tuvieron que partir al exilio como consecuencia de la guerra civil. En su caso, lo haría en compañía de su hermana Andrea y de su padre, el célebre escritor autor de obras como Míster Witt en el cantón o Réquiem por un campesino español. Los Sender Barayón arribarían en marzo de 1939 a Nueva York, convirtiéndose el continente americano en su nuevo hogar. Los niños serían acogidos en calidad de refugiados por Julia Davis, quien terminaría por convertirse en su madre adoptiva, ya que Ramón J. Sender pasaría varios años en México, antes de instalarse definitivamente en Estados Unidos.

Ramón Sender: my father would never talk about my mother. He may have talked a little bit to my sister about it at one point. I had trouble communicating with him because his English was very bad and my Spanish did not exist. There was one moment when we were in a bar together in Los Angeles, on a trip I took down there and we had a drink at the bar and I asked him "what really happened to my mother?" And he started talking, he was talking and he got very emotional as he went talking. Between the noise in the bar, his broken Spanish, my lack of Spanish I could not understand a word he said. I'm standing there like an idiot, with him telling me probably everything I wanted to know and I unable to understanding him. It was one my most frustrating moments.

- Audio: Ramón Sender. Worldfood VII, Locust (1965/2004)

Como se puede adivinar la relación del escritor con sus hijos fue cuanto menos distante y marcada por la incapacidad de Sender padre para hablar sobre las circunstancias en que murió su esposa. Hasta el punto de que llegaría a oponerse a la idea de que su primogénito escribiera un libro sobre ella. Pero sus intentos fueron inútiles, A death in Zamora se publicaría en 1989, traducido en España al año siguiente como Muerte en Zamora. En el libro son varias las hipótesis sobre el porqué de ese silencio, aunque todo apunta al remordimiento de Ramón J. Sender por haber recomendado a Amparo que se refugiara en Zamora al inicio de la guerra civil, mientras él se unía a las filas republicanas. Sería precisamente en su pueblo natal, donde Amparo Barayón sería fusilada, corriendo la misma suerte que sus hermanos Saturnino y Antonio, ambos vinculados al Frente Popular.

El trabajo de investigación que constituye la base de Muerte en Zamora no tuvo lugar hasta después del fallecimiento de Sender padre en 1982. Al poco tiempo Ramón hijo decidió viajar a España en compañía de su esposa, que le serviría de intérprete, en busca de testimonios que le permitieran comprender aquello que le había obligado a permanecer "exiliado por toda la vida de cualquier recuerdo de su propia madre." (Ramón Sender Barayón. A death in Zamora. Calm Unity Press, 2003, p. 17) El viaje, como prueba el libro resultante, sería de lo más esclarecedor, pese al imperante mutismo inicial. Un ejemplo de ello lo daría una de las primeras réplicas que recibió su petición de ayuda en el diario El País, donde un lector que declaraba haber conocido en vida a Amparo, le invitaba a mantener el mismo "tupido velo de silencio" de su padre argumentando lo siguiente:

"Lo mejor que usted debiera hacer en estos momentos sería acatar tal deseo, dejándolo transcurrir por el apasionante y lento trayecto histórico, quien en última instancia resolverá con el tiempo la compleja, complicada y comprometida maraña de una época que por reciente no resulta aconsejable clarificar." (Román de la Higuera Alonso. Contestación al hijo de Sender. El País, 3 de marzo de 1982)

Por desconcertantes que puedan resultar estas palabras no hay que olvidar que una de las cosas que aprenderá Ramón Sender en su regreso a España es que entre los verdugos de su madre se encontraban personas tan cercanas a ella como un miembro de su familia política e incluso un antiguo pretendiente rechazado. Pero como ha apuntado la historiadora Paloma Aguilar, los primeros años ochenta en nuestro país estuvieron marcados por la idea de evitar repetir el conflicto, "orientando la mirada hacia el futuro y concentrando esfuerzos en la estabilización de la democracia y en la integración en Europa." (Paloma Aguilar Fernández. Políticas de la memoria y memorias de la política. Alianza Editorial, 2008, p. 34)

Ramón Sender: what my father used to say was "I can forgive but I cannot forget." And I think that's probably the attitude I also have had and I think many others too...

2. Sonics y los inicios del San Francisco Tape Music Center

- Audio: Allen Ginsberg. Howl, Fremeaux & Associés (1959/2016)

Escuchamos la voz de Allen Ginsberg recitando Aullido, poema generacional que fue leído en público por vez primera en la Six Gallery de San Francisco en el año 1955. Por entonces una ciudad en plena efervescencia cultural que en la bisagra de los cincuenta y los sesenta pasaría de acoger a los escritores beat procedentes de Nueva York a hacer lo propio con sus herederos directos, los defensores de la contracultura y el movimiento jipi.

Ramón Sender llegaría a la ciudad en 1957, el mismo año en que Ginsberg era objeto de un proceso judicial por obscenidad a causa del poema antes mencionado, que a la postre terminaría otorgándole el pasaporte a la inmortalidad literaria. Sender era un joven estudiante de música que venía huyendo de la estrechez de los círculos artísticos neoyorkinos atraído por la promesa de libertad de San Francisco. Un par de años más tarde tomaría la decisión de trasladarse allí a fin de continuar sus estudios universitarios.

En cierta forma, Ramón seguía los pasos de su madre Amparo, que también había sido pianista. En su adolescencia Sender estudió bajo la tutela de George Copeland, un especialista en Debussy, algo poco habitual en Estados Unidos para la época. Además había realizado una estancia formativa en Europa que complementó con clases a cargo de luminarias como Elliot Carter y Henry Cowell. Sin embargo, cuando Ramón descubrió la música electrónica sus aspiraciones de hacer carrera como pianista se desvanecieron.

- Audio: Karlheinz Stockhausen. Gesang der junglinge, LTM (1956/2013)

Ramón Sender: my first exposure to electronic music was a concert in New York in 1956 put on by the league of composers and on the concert was Stockhausen's just completed piece Gesang der junglinge and also on the concert were Louie and Bebe Barron who had done the first electronic score for a feature film called Forbidden Planet. The Stockhausen's piece Gesang der junglinge just knocked me out, I was just absolutely amazed by that piece of music. And also I enjoyed the lecture and demonstration by the Barrons and I would say the Barrons and Stockhausen are responsible for my getting involved. The minute the concert was over I went out and rented a wire recorder. They actually recorded on a thin wire and I could rent one of those, I rented one and started fooling around.

- Audio: Pauline Oliveros. Time Perspectives, Important records (1961/2012)

Una vez instalado en San Francisco, Sender se matriculó en el conservatorio local inscribiéndose en los cursos de Robert Erickson, un compositor que enseñaba en dicha institución y que se convertiría en una suerte de mentor para buena parte de sus alumnos. En sus clases se prestaba especial atención tanto a la improvisación como a las posibilidades que ofrecía experimentar con la manipulación y el collage de registros sonoros en cinta magnética. Dos aproximaciones a lo musical, que pese a su disparidad, terminarían convirtiéndose en una constante en las creaciones de los artistas vinculados al futuro San Francisco Tape Music Center.

Ramón Sender: what I liked about tape music is it gave the composer the same freedom as the painter. He could put a stroke on canvas, in this case, it would be a sound on tape and then sit back and immediately hear it. He didn't have to go rushing down the hall and grab the cello teacher and say "please, please, try this part" and see if it works which was the way I used to. Even when I was a student there I would write a part for an instrument and I grabbed the teacher and had it tried it out. In this case I didn't need an intermediary, I could hear the sound on the tape and decide if I liked or not, it was a wonderful freeing. It freed me from those dots on paper that I've been making for so many years. It freed me from the attitude of the performer who I would have to convince to play it. So many times they were not interested in playing my music. So anyway, that is why, how I got into it as a classical trained composer, and I should say overly trained because I started very early studying with various people and I don't think it did me any good. I think it just froze me up, I mean there was a point when I was 20 years old, I'd be sitting in front of my music manuscript, put a note down and I would say "Now, what would Stravinsky think of that note? What would Schönberg think of that note?" and by the time I decided it had slowed me down a lot. I lost any sense of spontaneity about composition by having too many teachers.

I was saved from all this by the tape recorder and also by finding a very good teacher finally, after having studied with Elliot Carter, Henry Cowell and Harold Shapiro, in Rome at the conservatory. The man I finally found out here in California, his name was Robert Erickson, had been recommended as a very fine teacher and indeed he was. He specialized in encouraging students to improvise, so we had improvisation sessions which then turned into a group of students or ex-students meeting on their own: Pauline Oliveros, Terry Riley, Loren Rush, Phil Windsor. They are all people who either studied with Erickson still came by and visited the class or people I knew in other ways, but Pauline and I became very good friends, Terry and I also, except Terry left for Europe surely after that year and spent a number of years in Europe. So that's how things got started, I decided to invite my closest composer friends to create a new piece in this new studio at the conservatory attic and then for the first concert, of what I planned a year of concerts, I had new works by Pauline, by myself, by Terry and by Phil Windsor.

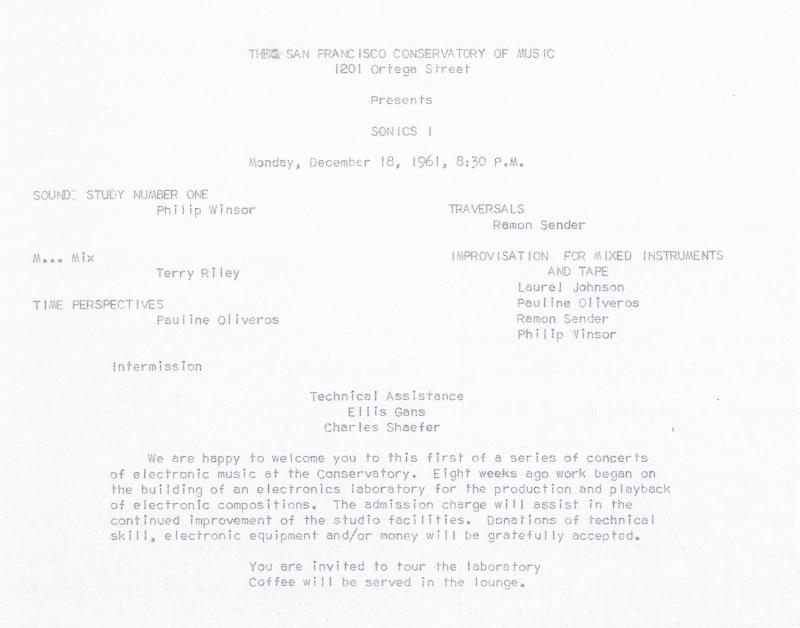

La fascinación de Sender por la música para cinta magnética le llevaría en octubre de 1961 a construir un estudio de grabación en el ático del conservatorio con un equipo algo limitado. A pesar de la economía de medios, el estudio permitiría producir varias piezas electroacústicas, muchas de las cuales serían estrenadas a lo largo de un seminal ciclo de conciertos llamado Sonics. Así, entre diciembre de 1961 y el verano de 1962, el propio conservatorio de San Francisco acogería estas sesiones cuya programación daría cabida a composiciones como, por ejemplo, este Time Perspectives de Pauline Oliveros que suena en estos momentos, la cual fue presentada en la inauguración del mencionado ciclo.

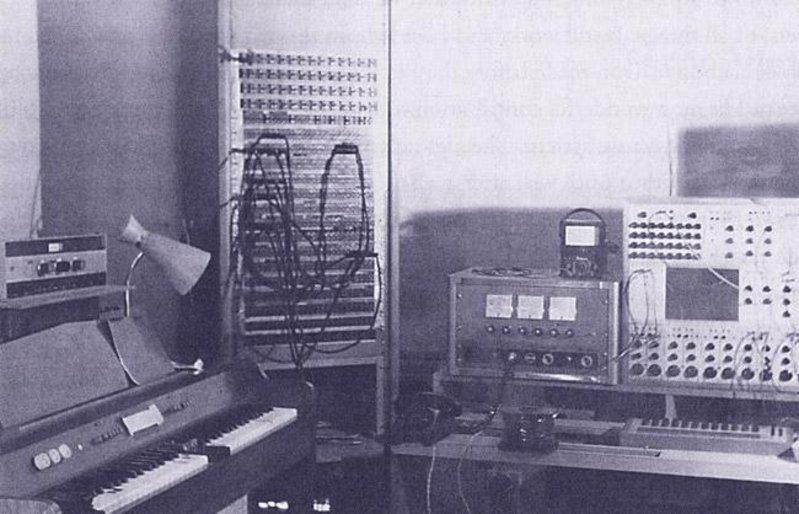

Ramón Sender: in terms of the attic studio at the conservatory I had not visited other studios and the sources of information I had were a few descriptions in books perhaps, there weren´t many books around but perhaps that, but mainly I just knew what I needed was as many tape recorders as I could afford and some things that made noise. So I had two or three tape recorders, one of them, two of them professional quality I would say, and then a small mixer and then I had an upright piano, just the strings and the soundboard that I could use for echoes, as I would put a microphone in one end and push the speaker up against the soundboard and then I would echo sounds through the piano and then what else did I have? I had an old bed frame, a wonderful iron bed frame that I put a magnetic microphone on it, and if I stroked it with a stick, it sounded like all the bells of Venice going off at the same time. It was a wonderful sound. I worked with what I called found sounds. Since I didn't have the technology for the fancy equipment, I turned to what was available.

- Audio: Ramón Sender. Kronos, Other Minds (1962/2016)

Otra de las composiciones creadas en el ático del conservatorio de San Francisco sería Kronos, una de las primeras piezas elaboradas por Sender desde este singular laboratorio sónico y que sería estrenada en la tercera sesión de Sonics, compartiendo programa junto a piezas de Stockhausen, Mauricio Kagel y Luciano Berio, cuyas cintas fueron probablemente cedidas por el propio Berio que en aquella época era profesor invitado en la universidad de Mills y al que Sender conocería gracias a Morton Subotnick, otro de los primeros asistentes a este ciclo de conciertos y futuro aliado y colaborador.

Ramón Sender: so for my piece Kronos, the piece starts with a sort of a white noise sound, it's really me dragging a pair of scissors over an aluminum sheet that gave this kind of white noise shimer and later in that same piece there is sort of a slowed down water sound that I recorded in the conservatory bathroom and slowed down the water. And when you slow it down enough it begins to sound like tablas, like the Indian drums, and I really like that so I added that to the piece. I was doing a lot of, “whatever I could find that interested me sounds,” so I suppose you would say we were more a musique concrete studio than we were electronic because we just didn't have the equipment.

One of the first things I did when I started the studio at the conservatory is I took some of their official letter paper with their logo and I wrote requesting donations to every major company I could think of. And of all those letters I must have sent out thirty, the only one who responded positively was Hewlett Packard who sent me two sine wave and one square wave oscillators. It was very generous. It was obviously a donation to the conservatory but it was a very generous thing for them to do and we got a lot of use out of those oscillators. In fact, in this piece Kronos I decided to use the oscillators as a performing instrument so I'm sitting there, it has a large dial on it... I tried to play melodies on it. So that piece involved that and the conservatory choral group come up to the attic and I said now "I just want you make a lot, improvise a lot of sounds together and I'm gonna record you as a source". So they did and then I took those sounds of their voices and put them through the upright piano as a resonating echo chamber and I was able to get these bursts of vocal sounds that go "ahhh" and fade away very slowly "ahhh." So those were my basic resources: the oscillator melody, the bursts of voices through the piano's strings echoing, the slowed down water and the white noise. Those were all my different sounds as I recall.

- Audio: Ramón Sender. Kore, Locust (1961/2006)

Aunque el ciclo de conciertos Sonics fue todo un éxito, Sender no encontró respaldo por parte de la dirección del conservatorio para financiar una segunda temporada. Así que Ramón decidió sumar fuerzas y equipo junto a Subotnick, ya que éste poseía un modesto estudio casero desde el que había comenzado a experimentar con la composición en cinta magnética creando bandas sonoras para piezas teatrales. De esta unión surgiría en el verano de 1962 el San Francisco Tape Music Center que fijaría su sede en una antigua casa victoriana en el barrio de Russian Hill. Desde allí se organizaría un nuevo ciclo de conciertos en cuya segunda sesión, en noviembre de aquel mismo año, se incluyó otra de las creaciones de Sender realizada en el estudio instalado del conservatorio, Kore, una pieza de elaboración similar a Kronos. En este caso dedicada a su hija Xaverie y cuyo título hace referencia a la diosa griega Perséfone.

En la primavera de 1963 el San Francisco Tape Music Center cambiaría de ubicación, esta vez al 321 de la calle Divisadero. El traslado a un inmueble mayor trajo consigo la invitación a compartir alquiler y espacio de trabajo junto a otros creadores de la escena local, como la emisora de radio KPFA así como la compañía de danza de la coreógrafa Ann Halprin, en la cual Subotnick desempeñaba la labor de director musical.

De esta manera, se desmarcaban de la rigidez habitual del medio académico, supliendo la falta de recursos con la promesa de facilitar el acceso a todo aquel músico que quisiera disponer de sus instalaciones, con el fin de que su creatividad no se viera cohibida ni por las expectativas propias de los círculos especializados ni por el público. Ahora bien, esta libertad concedida al creador no debe confundirse con una defensa del individualismo, ya que la apertura del San Francisco Tape Music Center partía del anhelo de implicarse en la vida musical de la comunidad, de manera que participase de la transformación de su entorno cultural.

Ramón Sender: I was thinking back to the days of guilds, of course we had the musicians’ union and the unions are an attempt to keep the guild concept going except in most cases musicians’ unions don't help that much. My idea was to have a group of composers and performing musicians who could be approached by anyone in the city needing someone for whatever reason. We began to do this a little bit, we traded music for plays to the biggest drama group here in the city. We said: “we'll do music for your plays in return for an introduction to your best sponsor”. So they introduced us to the woman who they felt would be friendly to some of our projects and she did help us and buy a piece of equipment and in return we did the music for three of their shows. That kind of deal was what I was hoping we would see more of. I mean ...we were not a commercial studio, but every once in a while, somebody would call us up with a small job that would pay us a little something. The idea we had... we also at one point had the idea that we would not list the composers on the programs, we would list the pieces but basically the composers would be anonymous and that was a thought that came and went very quickly but it was part of, I think, the same idea, the music was important and not the personality.

3. Multimedia y psicodelia. De Desert Ambulance al Trips Festival

- Audio: Ramón Sender. Desert Ambulance, Locust (1964/2006)

El San Francisco Tape Music Center más allá de ser un espacio para la producción de música electroacústica pasaría a convertirse en un lugar desde el que se promovía la creación multimedia ya que sus conciertos tenían un importante contenido escénico. Por un lado, porque podían contar con la presencia de los bailarines de la compañía de Ann Halprin, cuyas coreografías se entrelazaban con los collages de luz esculpidos en tiempo real por, entre otros, Anthony Martin, un pintor que había renunciado a los lienzos para experimentar con la imagen en movimiento y que prefiguraban los light shows de los conciertos del incipiente rock psicodélico. Danza y proyecciones que en ningún caso deben ser entendidas como un mero complemento visual a las piezas musicales. Más bien al contrario, pues se trataba de trabajar de forma conjunta desde distintas disciplinas en busca de una propuesta multisensorial y hasta cierto punto impredecible.

Como ejemplo citar una composición estrenada en febrero de 1964, Desert Ambulance, que el crítico Alfred Frankestein definió en su día como una muestra de "arte pop aural" mientras que su propio autor, Ramón Sender, la describía como "un vehículo de piedad enviado al páramo de la música académica." (David Bernstein (ed.). The San Francisco Tape Music Center. 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-garde. University of California, 2008, pp.23-24) Desert Ambulance sería concebida teniendo en mente a Pauline Oliveros como solista, que tocaba el acordeón sobre una pieza para cinta magnética mientras su cuerpo se convertía en una pantalla sobre la que se proyectaban las imágenes creadas por Anthony Martin.

Ramón Sender: the title Desert Ambulance came from a pile of garbage that some Christian missionary group had cleared out of their office downtown. I found these photographs, and one was titled Desert Ambulance and it showed an ambulance with a bunch of black natives in some sort of uniforms, they’re obviously ambulance people. The title stuck with me, unfortunately I lost the original photograph, I wish I still had it, I looked all over for another copy but never found it. It was years after I created the piece that I connected desert ambulance to the memory of my sister and I being evacuated by the French Red Cross from Zamora and I thought, well that ambulance must have impressed me as a little boy and that's why this memory trace lingers in my mind and that's how I picked the name for the piece. It's a far connection but it was one that meant something to me at the time and then, as far as how I created the piece we saw an advertisement, somebody was selling this unit called the Chamberlin in the San Francisco paper and it turned out the man was a doctor, he was an MD of a well-known San Francisco family. Morton Subotnick and I went out there and looked at the Chamberlin and we didn't know what it was and sure enough it was interesting, it had a tape player back under every key on the keyboard so when you press the key down, it was like a precursor of the mellotron. I'm not sure if the mellotron uses real tapes but the Chamberlin used a 3/4 inch 3-track pre-recorded tape under every key and you can select the track, and you can then have a trumpet or you can select another track and have a voice, it also had a rhythm section, you could key into that. Both Morton and I were interested in the unit because we thought maybe we can record our own sounds into it. So, we asked him: “Can we come back and make some tapes?” So we did, we both we made tapes. And those source tapes I made there were the ones I used to create the piece Desert Ambulance for Pauline. Then I decided that the live performer, the accordionist, would make electronic sounds or voice sounds, voice duplicating electronic sounds and all the instrumental sounds would be on the tape from the Chamberlin. I wanted to do projections on the performer, the performer was dressed in a white laboratory coat. The film projector had a specially cut aperture, it was carved to be the size the person sitting there. I didn't want any projection spilled behind her and otherwise I wanted the film to be only on the person with no extra. That worked very well and then we could have the earphones on Pauline, I was telling her what notes to play. Her score was dictated to her over earphones since it was too dark for her to follow a manuscript score. So, I'm on the score, I'm saying "there's a low b flat coming, please play the b flat with it or make the following vocal sounds." So I was making vocal sounds for her to copy, that was the tape the audience was not supposed to hear obviously and they were hearing the Chamberlin's sounds and the live accordion. So that was basically it, and then Tony [Martin] did a very nice score for it which he later adjusted so that the piece could travel and be presented in other places without either he or me present. See…up until then of course we would need a live projectionist but with his special score it could be done on a video projector along with the tape, so it was basically the idea. But it turned out to be a popular piece and Pauline did a number of times and then a couple of other accordionists have done it also.

- Audio: John Cage. Atlas Eclipticalis with Winter Music, Electronic Version, New World (1964/2014)

Rápidamente, en menos de tres años, el San Francisco Tape Music Center se convertiría en uno de los lugares más prominentes en lo que a creación experimental se refiere, siendo el evento conocido como Tudorfest uno de los hitos más importantes en su breve historia. Entre marzo y abril de 1964 se programó una serie de conciertos dedicados a David Tudor, el interprete predilecto de John Cage para sus composiciones. Del propio Cage sonaron varias piezas durante el festival, como este Atlas Eclipticalis cuya interpretación fue llevada a cabo por un grupo dirigido por Sender al mismo tiempo que el propio Tudor tocaba al piano otra composición: Winter Music.

Ramón Sender: this was really Pauline's project. I think she had met David Tudor. They together decided to do a week of Cage's music and other music also. I think it was a series of 3 concerts repeated twice each and we approached the radio station, KPFA: “would you be willing to live broadcast? Yes”, they were happy so they came in to do the live broadcast. Different of us took different jobs, I was invited to conduct one of the Cage's pieces. Towards the end of the week, John Cage came by, he was very nice, very open to everything, he wanted to hear all our music, what we were doing…he was very charming and then David Tudor became good friends with everyone including our technician. The Cage's thing was good for us, it made people take notice of us within the larger musical community, the more symphony-art museum crowd because The New Yorker had had a large article on John Cage that summer and suddenly he was fashionable among the fashionable crowd. In fact, the ladies’ auxiliary of the museum called us up and said: "please, would somebody come down here and talk to us about John Cage cause we are going to have a concert of his”. So I went down and talked to these coiffured, well-tailored ladies about John Cage and it was ok. We were getting pretty well-known in the city, whenever a composer visited, the official welcoming committee from the city would send him to us, so we had a lot of visits from various dignitaries, which was nice. Stockhausen came by and Usachevsky from the Columbia Princeton Center came by, a whole of group of young Swedish composers came and they came on Swedish government grants to study with us and we were so impressed that a government were actually paying these young composers to come and be with us, that was so enlightening that we just couldn't believe it.

- Audio: Morton Subotnick. Silver apples of the moon, Wergo (1967/1997)

David Tudor sería uno de los primeros en interesarse en otro de los grandes hallazgos producidos en el seno del San Francisco Tape Music Center, los módulos de lo que terminaría siendo la serie 100 del instrumento llamado Electric Music Box, uno de los primeros sintetizadores disponibles comercialmente, aparecido en 1964 y que terminaría siendo conocido con el nombre de Buchla, en honor a su creador.

Don Buchla tenía formación en ciencias físicas y música y le interesaba la electrónica así que Sender y Subotnick le encomendaron la tarea de diseñar un instrumento radicalmente nuevo que transformaría la manera de aproximarse a lo musical en años venideros y que Subotnick popularizaría en obras como The Wild Bull o sobre todo Silver Apples of The Moon.

Ramón Sender: we put an ad in the paper looking for an engineer, which brought some pretty funny people but then Don Buchla showed up and he claims he just came to a concert, he wasn't answering an ad or anything but we immediately grabbed him. We described what we wanted and I must say that really Mort took the main... he was the main designer, shall we say, for what Buchla was going to do. I sat in there and I told Morton I wanted too but I wasn't, at that point, I was more interested in... Morton was more interested, I was interested too but just in a more general way. I think at that point we got the drama group we were doing music for, we got their patron to give us a check and that is the way I think we got into the Buchla. Six months later Don showed up with a couple of modules and we were very excited and that was the beginning of what became the Buchla box. And Morton was the one who didn't want a keyboard, a standard keyboard, he was a clarinetist, he didn't particularly like keyboards and I don't blame him. He thought what we ended up with was a lot more flexible and I think he's right, the keyboard would have locked us into an older way of looking at things and was good not to have it and other than that the Buchla box could be used in live performance. I think Subotnick has certainly proved that the Buchla can do live performances very well. His whole career basically now is based on creating a new version of the piece every time he performs it. The machine, Buchla was flexible enough so could be used as sound source for preliminary tapes for creating a piece or could be used live in an improvisation live concert.

- Audio: Ramón Sender. Xmas me, Other Minds (1968/2016)

Escuchamos una grabación de diciembre de 1968, uno de los escasos registros de Sender a los controles del sintetizador Buchla. Una de las primeras demostraciones públicas de este instrumento acontecería dos años en el marco del Trips Festival que tendría lugar en enero de 1966. Un proyecto que pretendía abordar la experiencia producida por las drogas psicodélicas a través de la expansión sensorial que permitía la creación multimedia, ya fuera por medio de la música, el cine experimental, los light shows, la danza o el teatro. El evento fue una iniciativa conjunta de Sender junto a Ken Kesey y Stewart Brand. Kesey, era una figura cercana al movimiento beat, responsable del grupo conocido como los Merry Pranksters, una suerte de comuna que recorría Estados Unidos a bordo de un autobús difundiendo el potencial liberador del, por entonces legal, LSD. Por su parte, Brand pasará a la historia por ser el autor del Whole Earth Catalog, una guía imprescindible para introducirse en el modo de vida propuesto por la contracultura. El festival se convertiría en una suerte de gigantesca performance en la que, entre otros, se darían cita los mencionados Merry Pranksters pero también Allen Ginsberg, así como grupos de rock como Grateful Dead o Big Brother, banda que más tarde lideraría Janis Joplin. De alguna forma el Trips Festival podía verse como una celebración colectiva de la comunidad artística más aventurera en la Costa Oeste, al tiempo que también uno de los actos fundacionales del movimiento jipi.

Ramón Sender: as time passed, I felt pretty burnt out by the concert format, I was kind of getting bored with concerts and wanted to do something different. Our friend Tony [Martin] who was doing our visual projections said you should talk to this guy, Stewart Brand, he's doing a multimedia show called America needs Indians. So I called Stewart up and we talked and we did have a lot of interests in common. And Stewart called me a week or so later saying Ken Kesey is in town, and Kesey is doing these acid tests. In fact, there was one that December at the Fillmore I went to. He wants to do a weekend , he is calling a Trips Festival which would be all the most interesting groups doing things in the city, bringing them all together, are you interested? Yes, I am, I don't know if the rest of my group is interested but I'll find out. So that was the beginning of collaborating on the Trips Festival which of course became a big deal. And I was playing from Kesey's idea: get together the groups during the best trips and put them all under the same roof for 3 nights. So when Stewart said: “what groups would you recommend?” I was living in Berkeley at that time, and I said there's a theatre group here, it is quite good, doing the same thing with theatre that we were doing with sound, so I invited them: they were Ben and Rain Jacopetti and they had a group called Open Theatre and in this Open Theatre various actors or groups would perform. So they came in and the idea was each group would bring a rock band, so the Jacopettis decided to bring a Berkeley rock band called The Loading Zone. I had contact with Big Brother who had been, not directly involved with the Tape Center but indirectly involved. Later Janis Joplin came to some or our events, but Big Brother at this time did not have Janis, this was pre-Janis but I did invite them. I said "we need a band as part of our evening at the Trips festival, would you be the band?" and they said yes. So then we had Big Brother, we had Loading Zone, and of course Kesey and the Merry Pranksters came in with the Grateful Dead. I don't think Stewart brought a band, he set up a tipi in this large auditorium and he had these projections and music. The weekend was unusual and really unique and brought together groups of people who had not been in contact with each other. And suddenly everybody was looking around thinking "my god, it's not just me, it's really happening" and there was a lot of that feeling that year. We had a lot people, all of our regular people came and a lot of our friends and filmmakers we were in contact with, we called them up: Bruce Bailey, Bruce Conner, number of others they all came and projected films from the balcony as part of the show on one night and anyone who was in all connected with us showed up plus of course many many other people. Ann Halprin came with her dancers, set up a huge cargo net, they used to pull cargo on the ships, they had it hanging from the ceiling and they were climbing, the dancers, climbing on the net. Stewart Brand brought a friend who was a professional trampoline artist and set up a big trampoline and then put a strobe light on the trampoline so he was doing these incredible gymnastics in the strobe, it was really amazing. Anyone in the art community in San Francisco who had any interest was there I'm sure.

- Audio: Grateful Dead. It's all over now baby blue, Rhino (1966/2003)

El Trips Festival también puede verse como el inicio del fin del San Francisco Tape Music Center. Por un lado, porque el centro recibió una importante subvención por parte de la fundación Rockefeller, la segunda en el plazo de un año, lo que comportaba la obligación de afiliarse a una institución académica, mudándose a la Universidad de Mills, en California, en el verano de 1966. Por otro lado, porque para entonces Morton Subotnick había decidido mudarse a Nueva York, mientras que Ramón, tras un retiro en el desierto dedicado a la meditación, prefirió abandonar la escena y cambiar de prioridades abrazando el modo de vida tribal de las comunas Morning Star y Wheeler, donde seguiría entregado a la creación musical por otros medios y con otros fines, al menos hasta entrada la década de los setenta. Ante la marcha de los dos miembros fundadores, Pauline Oliveros asumiría la dirección de esta nueva etapa del centro secundada por Anthony Martin y William Maginnis. El San Francisco Tape Music Center pasaba a convertirse en el Mills Tape Music Center. Se cerraba así un episodio en la vida de sus protagonistas y daba comienzo a toda una multiplicidad de nuevas historias, cuyos ecos aún pueden sentirse en nuestros días.

Bibliografía:

Paloma Aguilar Fernández. Políticas de la memoria y memorias de la política. Alianza Editorial, 2008

David Bernstein. Music from the Tudorfest: San Francisco Tape Music Center, 1964. New World, 2014

David Bernstein (ed.). The San Francisco Tape Music Center. 1960s Counterculture and the Avant-garde. University of California, 2008

Francisco Caudet. ¿De qué hablamos cuando hablamos de literatura del exilio republicano de 1939? Arbor, vol. 185, nº 739, 2009

Francisco Caudet. El exilio republicano de 1939. Cátedra, 2005

Román de la Higuera Alonso. Contestación al hijo de Sender. El País, 3 de marzo de 1982

Ramón Sender Barayón. A death in Zamora. Calm Unity Press, 2003

Ramón Sender Barayón. Llamada del hijo de Sender. El País, 13 de diciembre de 1981

Ambulancia en el desierto es una serie de tres cápsulas dedicadas a Ramón Sender Barayón (Madrid, 1934), un nombre tan familiar como poco conocido en nuestro país. Se trata de un intento por recuperar su figura atendiendo a su contribución musical, en particular aquella que llevó a cabo en la primera mitad de la década de los sesenta desde el San Francisco Tape Music Center, una institución pionera que Sender fundaría en 1961 junto a Morton Subotnick y que, pese a su breve existencia, constituye uno de los capítulos más fascinantes de la historia de la música electroacústica, e incluso, si se quiere, de la creación multimedia.

Sin embargo, para realizar una aproximación a este autor resulta obligado abordar el hecho de que si Ramón creció en Estados Unidos fue como consecuencia de que su familia, su padre era el célebre escritor aragonés Ramón J. Sender, se vio forzada a dejar España en 1939. Su madre, la pianista Amparo Barayón, corrió peor suerte y perdería la vida a manos de las fuerzas franquistas poco después del comienzo de la Guerra Civil. Un suceso acontecido en extrañas circunstancias y rodeado por un silencio con el que Ramón tendría que vivir para siempre.

Estas tres capsulas recogen el testimonio del propio Sender, entrevistado para la ocasión, y lo complementan con varios registros de sus composiciones así como las de algunos de sus coetáneos y compañeros de viaje. Todo ello tomando como marco de referencia el relato que un estudioso como David W. Bernstein elaboró a partir de su investigación en torno al San Francisco Tape Music Center, desde sus inicios hasta su apogeo, previo a la dispersión de sus miembros, paralelo a la emergencia de la contracultura y la psicodelia en la Costa Oeste norteamericana.

Si como ha señalado Francisco Caudet la literatura española de posguerra necesita historiarse no solo en términos puramente territoriales sino también extra-territoriales, dadas las circunstancias que obligaron a miles de españoles a abandonar el país (Francisco Caudet. ¿De qué hablamos cuando hablamos de literatura del exilio republicano de 1939?, Arbor, vol. 185, nº 739, 2009), Ambulancia en el desierto pretende hacer lo propio con un compositor cuya obra está inevitablemente ligada a este episodio responsable de truncar la trayectoria del siglo XX español.

Foto de grupo. San Francisco Tape Music Center. De izquierda a derecha: Tony Martin, William Maginnis, Ramón Sender, Morton Subotnick y Pauline Oliveros.

Programa de Sonics. 18 de diciembre de 1961

Estudio del San Francisco Tape Music Center con el primer sistema Buchla a la derecha (finales de 1965, principios de 1966). Desde la izquierda: Chamberlin Music Master, Patch Bay, amplificadores auxiliares y la caja de Buchla. Fotografía de William Maginnis.

Compartir

- Fecha:

- 09/09/2016

- Realización:

- Rubén Coll

- Agradecimientos:

Ramón Sender Barayón, José María Llanos y José Manuel Costa

- Licencia:

- Produce © Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (con contenidos musicales licenciados por SGAE)

Citas

- Moritz Rosenthal. Prelude for piano, Op. 28: no 13 in F sharp major, APR (1937/2012)

- Ramón Sender. Worldfood XII, Locust (1965/2004)

- Ramón Sender. Worldfood VII, Locust (1965/2004)

- Allen Ginsberg. Howl, Fremeaux & Associés (1959/2016)

- Karlheinz Stockhausen. Gesang der junglinge, LTM (1956/2013)

- Pauline Oliveros. Time Perspectives, Important records (1961/2012)

- Ramón Sender. Kronos, Other Minds (1962/2016)

- Ramón Sender. Kore, Locust (1961/2006)

- Ramón Sender. Desert Ambulance, Locust (1964/2006)

- John Cage. Atlas Eclipticalis with Winter Music, Electronic Version, New World (1964/2014)

- Morton Subotnick. Silver apples of the moon, Wergo (1967/1997)

- Ramón Sender. Xmas me, Other Minds (1968/2016)

- Grateful Dead. It's all over now baby blue, Rhino (1966/2003)