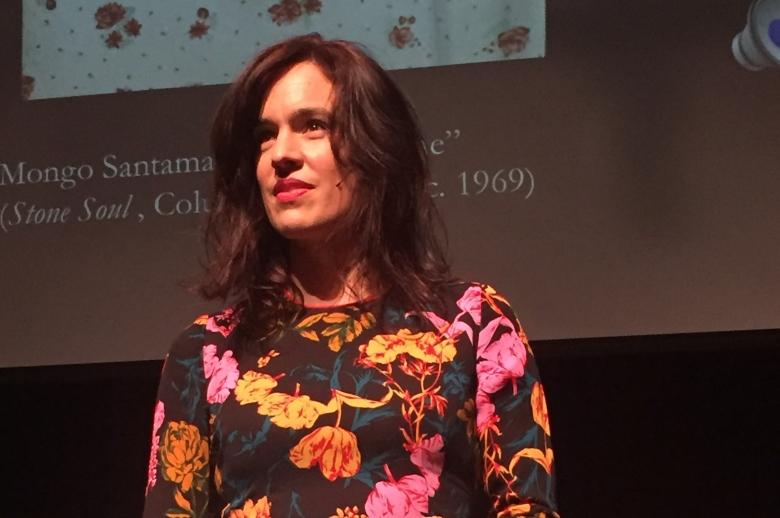

Alexandra T. Vázquez

Migration and Sound

Transcription

[Audio: Dafnis Prieto Si o Si Quartet. Thoughts. Dafnison Music (2009)]

Alexandra T. Vázquez: Some people might need demographic studies. I often just rely on songs to tell me about who's there, who's been there before.

Hi, my name is Alexandra Teresa Vázquez. I am a professor of Performance Studies at New York University. I dedicate my work and my life to the study of music and all that it gives us.

Migration and Sound

I was born and raised in Miami. My father had a very difficult migration experience coming from Cuba, alone, when he was 16. He ended up losing his parents and was basically stuck in the United States from 16 on by himself. So certainly, there's a kind of a soil in me that would pick up on certain forms or certain modes of melancholy that he might have.

My mom, though she grew up in northern Florida, also in some ways had a really intense migration history moving down to Miami. You know, the first person in her family to go to college, and to be in this insane, multicultural city like Miami, Florida, in the seventies, which was this insane party town, but also more and more becoming an immigrant majority city.

So, when I was growing up, for example, you have to remember Miami is in some ways the capital of the Americas in terms of migratory people. And so, for example, in my elementary school one year, because of the Mariel boatlift, suddenly my school doubled in size because there were these children who were refugees, who then needed a place to go to school. So, it was really literally seeing how space could accommodate or how my education could be enriched and not impoverished at all by the introduction of more bodies from other places. There are so many moments I can point to growing up: a kind of Haitian migration and Nicaraguan migration to Miami. All of these things I was very aware of growing up there.

And also, what's kind of amazing about growing up in Miami is that difference is almost like a banal condition. You know, everybody had parents from somewhere. Everybody embodied some form of difference. This is not to say that there aren't racial apartheids or real difficulties to do with racial segregation and wealth disparity, but it was a really incredible place to grow up and to give me that kind of sensibility.

So, I'm going back to my hometown because I saw in real time, I saw shows, festivals, that would have lineups like KC and the Sunshine Band, you know, disco, to Carlos Santana and Celia Cruz as the headliner. That's one concert that I remember, right, when I was 13 that I went to by myself, outside wearing a bathing suit; terrible, but it was to be a kid growing up and seeing all these people come together and the audience had no problem with the differences in the genres or the identification of the musicians. It's just we were kind of all in it together. And then more so the kind of sounds that were being produced, you could absolutely hear the Caribbean, the Cuban, the Jamaican, the Trinidadian, you could hear the Brazilian, you could hear soul, you could hear rhythm and blues all being mega-mixed into this kind of lava. And so those things always went hand in hand to me as migration and sound, because again I was just in the surround of it all the time.

Now, I did do my undergraduate. I did some time in Northern California at Santa Cruz in San Francisco. But the second half of my adult life, the majority actually, was in New York City, in Brooklyn, which was amazing because what I got to be around in New York was all the different Latino populations that were a little different than in Miami. So there was a much more heavy Boricua presence, a lot more Dominican Ecuadorians.

But to be in New York coming of age as an adult was also amazing because I'm getting this amazing education in this other island tradition that's happening in the northern metropole, like, you know, merengue, like bachata, like house music that's really coming out of New York that I adore. But also, as I was listening, as I would listen to like old house music in New York, I was like, wait, but isn't that from Miami, right? New York doesn't like to necessarily recognize that stuff is from other places. But, you know, my ear just was very well trained… that I was like, oh, but these. And so I had this intuition, like say... If I’m at a discoteca and I would hear certain songs and I was like, god, that sounds like so-and-so from Miami. And it was just my intuition. You know, I come to find out 30 years later that I interview the people that made that music and they said: “Oh, yeah, we did that session in New York” or, you know, “we recorded with so-and-so”. And so one can intuit these migrations and collaborations and stay with the intuition because they're often true.

And that's why it's great to just listen to as much different possible kinds of music, because it just gives you a repertoire to pick from to see… oh my gosh! they actually were working together, or there was an encounter here. And also seeing a lot of musicians from the colonias coming together and forming groups and what they bring there. Seeing New York transform into a deeply Mexican city because a lot of the recent migration of the last 20 years of Latinos have been Mexicanos. And suddenly cumbia feels perfectly appropriate as you're walking down the street, whereas before it was rumba, or salsa, or mambo. So I also love hearing the impact of this deep migratory movement in the sounds of how our cities feel.

You could easily translate this to the visual arts, right. As an easy example, if you think of the different painting techniques or, you know, formal adoptions that folks in Europe were taking from places like West Africa or the Caribbean, you can see this all the time. But for example, in Cuban music just instrumentally being able to hear the migrations of people in the music itself, like the corneta China in Cuban music that was brought by Chinese migrants to Cuba, and suddenly, boom! You have a whole history of people that very few people want to think about or know the history of. And there it is right there, stridently blasting our ears from the music as a presence.

So some people might need demographic studies. I often just rely on songs to tell me about who's there, who's been there before.

[Audio: Dj Fingerz & Cutmaster Knobz. Miami, that bass so strong. Pandisc (1991)]

Growing up while listening in detail

When I was in elementary school, you know, riding the school bus, it was a really formative place because the bus drivers would always put on these amazing radio stations that were live, active and super experimental and creative in Miami in the eighties. And I remember this one particular bus driver, Vilma, who, you know, had this radio station called Power 96 on. And there was this crazy kind of electro Miami-based song playing. And as she was turning the wheel, she was kind of dancing along to the song; as she was turning this huge wheel of a school bus.

And so I guess what made me think of that is from a very, very early age, music was not only something that I felt, but I observed in how people were experiencing it. And it's part of what makes me be completely enamored of people, even as a kind of species that disappoints me the most. But to see what Vilma brought with her as she was driving at this very early morning pick-up and how the music kind of kept her going or allowed her to make the turn. It's those kinds of flashes of memory that… It's just the music took hold of me very, very early. It's probably to do with my parents somehow.

As I kind of came of age and as I went to university, I would do things in high school, like, when I was in fourth grade, which is, you know, nine years old. I did a book report on Jimi Hendrix and it… just really kind of a weird kid who was very attached to a lot of different kinds of music. And I guess when I went to college I didn't know. It's really interesting because I came to college and the first course I took with this amazing mentor of mine, Anne Layne, was an introduction to Marxism. And, you know, it was slowly as I went into this other field called American Studies, where I was reading a lot of political theory, a lot of philosophy, but also Cultural Studies at that moment in the early nineties, which was very, very strong, and I was reading folks who were… at the time I called it writing smart about music, or they were able to create images of cities and place through the analysis of the music that they were talking about.

So I kind of was exposed to that and it really excited me a lot. There was some Chicanos writing about lowrider culture and sound and I was really influenced by that. But, as I came to produce my own work, I've always felt a kind of disappointment because the books, quote unquote, “about music”, that's like about music. I always left feeling a little... I don't know, there's a kind of poverty to it, and its “sensorum”. It's not necessarily work that moved me. And a lot of it - and it’s not accidentally authored — a lot of books about music are authored by straight men.

I always felt very frustrated that books about music had to take this very long vista and had to be almost encyclopedias of information. So the history of rock or jazz from A to Z, always in the form of a comprehensive guide, always in the “let me tell you everything about this thing”. That was a real frustration of mine. One, because my mind just doesn't work like that. My mind works in remembering details like Vilma or, you know, something in a song, a line in a song that I keep repeating over and over, or, as is still my habit, I'll get obsessed with one song and I might listen to it obsessively, like 2,000 times.

So it was never in me to be able to write the comprehensive book about music. So what I learned with my training and performance studies, what I kind of was given permission to do by my amazing advisor, José Muñoz, who is a really kind of foundational figure in queer of color critique. What I learned is that the writing that I wanted to do could be also an experiencing of that feeling that one gets when you're listening to something. Why does it have to be about the thing? Why can’t it be with the thing?

So for me, the detail becomes very, very important because again, I just get caught by them and I find that the problem with a comprehensive model about music or any art form, actually, is details are often raced and gendered. So, for example, in this history of contemporary art women and folks of color will often be relegated to a detail rather than an integral part of the story.

So for me, especially in the history of, you know, the histories that I work on in popular music, especially Cuban, Caribbean and Latin music, that woman performer might be a detail to one person, but for me she's a completely amplified catalog of an abundance of work. So details are portals, to me, of a kind of more holistic approach to music.

And in terms of listening, I see there's been a lot of kind of studies in listening. I think also in Europe, too, certainly in the Americas, a lot more studies are taking listening seriously. But I'm not so much into the kind of acoustical sciences of the ear or anything like that. For me, listening is fundamentally a deep intellectual and social practice. So as one might read carefully, I don’t know, Agamben. And the time it takes to read Agamben I take a similar kind of very difficult work of making my way through a particular album or something. And for me listening is something that has to be done with a lot of time, with tons of repetition, and living in that kind of repetition is also a great pleasure of listening.

Today I did a presentation for the museum where I played some songs that I have written about and published in an actual book. And as I listened to them with other people today, this whole other scene in Madrid, I heard details in those songs for the first time. They were making me laugh. I got goosebumps. So it's almost like they're always giving me gifts. They're always giving me kind of like silk purses of information.

[Audio: Son 14. Vamos, háblame ahora. Movieplay (1979/1981)]

Adorno and the biographical question

I guess I never cease to wonder at the capacity of people to go through the things that they go through and to still make beautiful things. I know it sounds very banal, what I'm saying, but I do really find just complete wonder in the experience of people's lives, their migration, who they met, what their moms did, who were their first musical influences? What were the first records they bought? All of those to me are historical questions because often the people I'm interviewing get erased from historical accounts. So there is this wealth of information about influence, about connectivity of tradition, of different populations coming together to make things, right? That really have only been brought to me by talking to people about their lives.

And again, my experiencing of music helps me to also see how others have experienced music in their bodies, in their souls, in their schools, in their families, in their friendship circles, in their discos... So the biographical question or biographical work is very, very important to me. I would say, however, I would say what I do is a kind of anti-biography in the sense of I'm not trying to get a definitive account of one person or their entire… Again, I can never be comprehensive about one person, ever. I could maybe take in a couple of details from their lives and play with them in the work and they inspire the work and move it into new directions. But there's very little in me that I could do a kind of chronological study of one human being from beginning to end, because I would always know that that's a failing project, because I wouldn't be able to know. I wouldn't be able to capture all of that. And so these biographical details that I include from interviews that I've done with people for me, again, are as fertile, as difficult, as theoretically complicated as reading somebody like Adorno.

[Audio: Theodor Adorno / Moscow Symphony Orchestra. Op. 4: No. 6. Sehr langsam, TYXArt (2013)]

I have this very funny attachment to Adorno. A lot of people focus on his disparaging kind of racist, ignorant really, work on jazz or popular music. But again, yes, that's true. But he has such an amplio body of work that that was like a kind of very ignorant, very European misstep. However, he is a gorgeous listener of Schubert and a gorgeous listener of Mahler and Beethoven. So here's my attachment: it’s how he listens. I really firmly believe in a lot of the political stuff that he was thinking about, too.

That part of our job as people is to keep thinking. And when we stop thinking, that's when genocide happens, right? I believe in critical thinking. As an activist project. But I actually… one of the future projects I want to do is not to use Adorno to rethink his thing on jazz. I don't care about that part of Adorno. I think it was stupid and terrible. But what might be really interesting for me as a scholar is to think about… Wow! the way that Adorno writes and listens to Beethoven is — really, you know, I'm not there yet — but I really feel a kind of kinship to how it is that I listen to Cuban music.

So disrupting the experimental and the popular binary to me is just as important in scholarship, too. Like it's important for me to be able to take somebody like Adorno and think really seriously about somebody, a percussionist like Changuito. And people are so attached to his political theory writings, or they only read Dialectic of Enlightenment. But the bulk of his work was about music.

And you know what's amazing to me about his kind of soft, bourgeois upbringing is that it was like super kind of queer in some ways because he grew up with two mommies, his mom and his aunt. And that's who in Adorno, what people don't see, is who trained his ear was this deeply maternal line of his mother and his aunt. He called them both mother. He called his tía “mami” and he called his mommy “mami”. But they were really important musicians. One was a pianist and one was a singer. And so you think about this little boy genius, right? Sitting at the piano while his aunt and his mom, his two mommies, are singing songs and playing together, accompanying each other. And to imagine him kind of in this matriarchal circuit of listening to me is how I read him. And a lot of people don't read him that way. I hear that matriarchal line in every way that he listens, even though a lot of folks would have a real problem with me saying that.

[Audio: Machito and his Afrocubans (con Graciela Pérez). Mi Cerebro, Tumbao Cuban Classics (Circa 1945-1947/1997)]

Dance matters: Disrupting the experimental and the popular binary

“Primero de todo me encanta bailar. Yo soy niña de discoteca, que es muy común en Miami”. When you have family parties “por ejemplo por un cumpleaños” and you have “los viejos y los jóvenes”, babies, grown-ups, everything. Let's say at a certain point in the evening people put on some music, as often happened when I was growing up, you would see old people and young people dancing on the same dance floor at the same time, which is beautiful. And on top of that, they would be dancing to music that was giving them almost historical truths about themselves that they might not recognize or might not want to recognize in their kind of actual life.

So a lot of the kind of amazing dance jams in salsa are directly about the tribulations of slaves. And so on the dance floors, which include my family, but also include many experiences in salsa clubs in New York or house clubs or any of that, is people are moving and they're also absorbing, again, lyrically, instrumentally, truths about the past.

And in some ways I often wonder, well, is that the only way we can really take in the historical truths about ourself, as if our bodies are in a kind of movement with those things alongside other people? So in some ways I think dance genres... It's just kind of my “gusto”, but I think it's also because there is a kind of recognition that happens in dance music of all forms that's different, that's visceral, that puts you in contact with other bodies. Sometimes that doesn't end up so peacefully or anything. But how you get to know how other bodies feel, how it is to be in a live crowd around bodies that are not yours, bodies that are differently abled, bodies that are from other places, folks that are shorter and taller than you, that speak different things.

For me, that kind of moving together for the most part has been extremely positive in my experiences. I know that there's moments where that can be very violent, but I'm not interested in that, that there's a different kind of absorption. Also, I can't separate the body from music at all. There's no way I can do it. People often talk about a disciplinary thing that actually does make me cranky, how people try to extract dance studies from music studies. How can you possibly do one without the other? Then you have these bifurcated feelings of people who are experts in dance and people who are, quote unquote, “experts in music”. And often the two never meet. And I don't know how I can do that without talking to my colleagues, who are beautifully articulating movement all the time. But there's no way I can think of music in a way that's not corporeal. I can't. A, because it moves me that way. And B, because, again, I've seen proof of it falling onto people. That music gets to fall on people when they're in the midst of a dance with it.

Also, there's this new thing “en los Estados Unidos” and I'm sure “acá también en Europa que se llama” sound studies, “estudios de sonido”. Part of the difficulty I have with that emerging field is it doesn't seem to think that the popular is interesting in an intellectual way, that the sounds that emerge in sound studies is kind of, quote unquote, “avant-garde music” or “experimental music”, where I hear experimental music as the popular all the time. All the time. And so sometimes sound studies can be often racialized or gendered in certain ways that, you know, if it makes kind of funny, idiosyncratic noises, it’s sound studies, but if you dance to it, it means it's popular music.

I want to completely undo that binary because within the popular, especially in the Cuban musical canon… first of all, most of the musicians are classically trained and already they're teaching me, by the way that they sound, by how they've been trained, that they're holding multiple traditions at once. Why can't I do the same? And it's very interesting.

A lot of the musicians I've talked to, especially Cuban ones like Yosvany Terry, Wilber Calver, Dafnis Prieto, these are all really great musicians. They don't think it's a big deal. For them, it's just almost like switching between different languages that they know very, very well. And I aspire to that fluency with all of this, with music, with dance. I just want to be fluent in all of it because all it can do is enrich my writing. Enrich my teaching, enrich my pedagogy.

[Audio: Sam Cooke. Feel it, RCA (1963/1985)]

Miami and the Florida Room

Yes… You see, there's a very… people, the image they have of Miami, for example, is, you know, a televisual one, you know, that's handed to them pretty much from the 1980s on and gives them this imaginary of Miami being this always emergent, quote unquote, “global city”, you know, that constantly yearns to be modern. And as part of that, there's also this assumption that it doesn't have any intellectual or aesthetic traditions and the real violence of that is when people say Miami has no culture, what they're not able to hear or they don't want to hear are the deep Black and indigenous histories that this place has.

So my book, The Florida Room, is this architectural phenomena that comes out of mid-century architects like Paul Rudolph, a very important, you know, kind of modernist architect. And he designed this space built for Florida that was climate friendly. This is before air conditioning. So how can… he wanted to make an addition to the house that allowed you to be outside and inside at the same time. So a kind of screened-off porch. It's not necessarily part of the main house, but it is, and, I say in the book, it is when you enter this space, there is some alterity required. It's a social space. It's not the dining room, it's not the living room, it's the Florida room. It's where breeze can come in and out. It’s, where I say in the book, it's where your aunt comes to stay for a month. It's your parents are getting separated and one parent might stay. It has all these kinds of complicated histories.

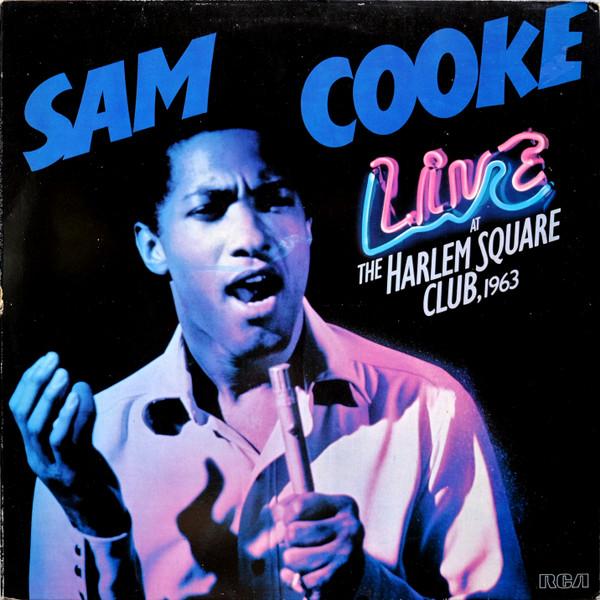

Well, for many, many, many years, since I was an undergraduate, I think I spoke about a project I did on Sam Cooke. It's this beautiful album he recorded live in Miami called Live at the Harlem Square Club, one of the most important live albums, to my ear, of all time. And it was recorded in Miami right before… the club that it was recorded in was in a historic Black place that's called Overtown, and they called it Broadway of the South. All of the main Black celebrities of the eras would go perform there, often because Miami Beach was segregated, and often they would go perform those gigs where Black people could not attend, and then they would go to Overtown in the after-hours and play for Black folks. And it was a real robust, beautiful, rich cultural history that happened there, but like in many other places in the United States, highways were built directly to obliterate these neighborhoods and one was built directly through it. So this has been something that has preoccupied my mind for literally decades. And I'd been doing little writings here and there about music for Miami, which has very deep rhythm and blues, soul, gospel traditions, but also super important Cuban, Caribbean, Miccosukee, Seminole musical traditions, too.

The problem is that I had to cut through two kind of big place fables. One is Miami as the kind of version of Miami Vice, the TV show, as the global city, but also this place that, quote unquote, “has no culture”. And at the same time, there are all these different... Like it's not just, quote unquote, “Black people”. We're talking about dozens of different cultures of Black communities. From different parts of the Caribbean, from the Bahamas, from the south, Georgia... Like there's all different kinds of Black cultures, plural, happening in Miami at the same time that you're getting these massive migrations, at the same time that the indigenous folks keep doing their work while all of this stuff is being built over, around them. There's also been a kind of writing apartheid with Miami; you know, folks will write a book about Black Miami or Cuban Miami or, you know, there hasn't actually been many books about indigenous Miami, but they kind of separate populations out.

And again, I don't think that's the truth of the place. And it's definitely not the truth in the music. So in order to organize, as a kind of spatial imaginary, I decided to kind of use and then corrupt the Florida Room as a spatial metaphor because I wanted everybody to be there. I wanted to just bring everybody in. I didn't want to put people in camps around identitarian rules, or I didn't want to put them in different camps according to genre rules. All of that stuff that keeps people apart because again, that's not true. Everybody worked with everybody in the time periods I'm thinking about. So the only way I could do that was to have a kind of room that was able, that was hospitable enough, that felt hospitable enough, to bring everybody in.

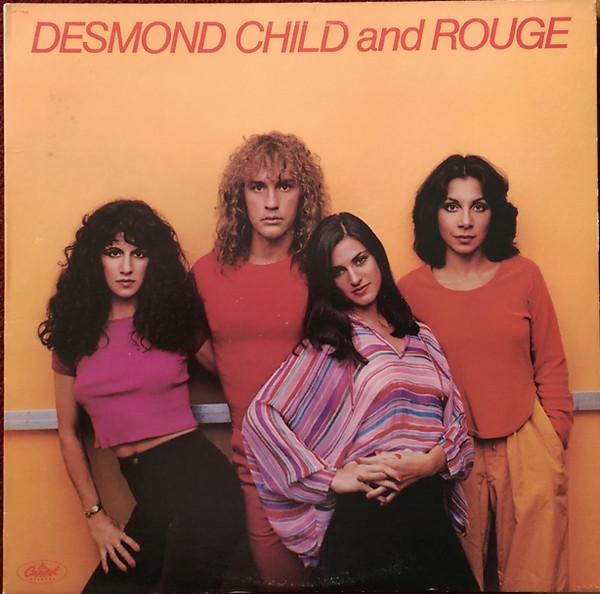

And again, I'm not trying to make a happy, shiny picture of this as if there's no conflict, no violence, no inequity, any of that stuff. But people constantly and consistently made music together. So I had to kind of put them all in one place. What I'm doing in the book is a little unusual because I'll pair like a Cuban musician like Desmond Child, a gay Cuban man, who is the songwriter with Jon Bon Jovi of Living on a Prayer. All kinds of huge rock anthems. I pair him with Tiger Tiger, which was a Miccosukee Indian rock band from the seventies. So these are people that are the same age that came of age together, but nobody has ever talked about them together, even though they were on the same circuits, because somebody might think of Desmond Child as Cuban or Tiger Tiger as being Miccosukee, but somehow they couldn't put them in the same room. I needed to do that. So the Florida Room was a way I could really just kind of gather everybody.

It took me like 20 years to figure out the structure of this book. So the history of Miami, that was really built as a city by immigrants from the Bahamas in the late 19th century and folks from southern Georgia. There's this thing in the United States called the Great Migration, where in the early 20th century, many, many African-Americans and Black people would move from the south to cities in the north because the South had such racial violence. Employment opportunities were terrible, folks were trying to flee a lot of the vestiges of slavery... But what doesn't get talked about very often is a lot of Black folks went to California and a lot of them went to Miami to make new worlds and to find maybe different sensations of freedom that they might not have experienced in the towns that they grew up in.

So my last chapter is on Miami bass, and in some ways it's the kind of bass that blows the whole book open, because that's how it actually sounds. And if anybody ever listens to this, please go, just figure out what Miami bass is, go YouTube it, it's everywhere. But it's a really important movement in music that continues to stay with us in very hidden ways. Is this insane? It’s this kind of explosion out of the R&B about Overtown that I was talking about earlier, those people that had to move that neighborhood because of the highways end up going to places called Liberty City. And even though the highway decimated these cultural locations, old people were still playing their music for the young people. And those young people who were listening to the rhythm and blues and soul of their parents or calypso or rumba, whatever it is, those are the kids who were the pioneers of making Miami bass. And this is now like in the early eighties. Miami bass has sort of a justified but an unfortunate reputation because the lyrics can be deeply misogynist and I say in the book, you know, they're very hard to take, especially if you have daughters like I do.

But, you know, it's really talking about really explicit lyrics about women's genitalia. It can be very bad, but the sound of it is what's important. It's the sound, because in bass, you know, one can hear the grave site that is the middle passage. So this sonar sound that comes from the bottom of the Atlantic of everybody who lost their lives there. It comes to kind of sound that way as it comes to be in the south of Florida and makes this kind of intense body-shaking and city-shaking and spatial-shaking interruption about everything we thought we knew about anything. So in some ways, Bass had to be the last chapter because it hopefully kind of rumbles the rest of the book and rumbles the walls of the Florida Room even more than I already tried to.

I mean, at the end of the day, as swirly as I sound or as, let's see, as much as I believe in following the migrancy of people and things, I also firmly believe as a writer in structure, so I needed a structure in order to house all of this stuff, but also so that housing could be blasted open. And people come in and out however they want and future readers and scholars can do whatever they want with it.

[Audio: Anquette. Shake It (Do the 61st), Lil’ Joe Records (1987/2000)]

Alexandra T. Vázquez is a researcher, writer and associate professor at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. Her work is centred on music, Caribbean aesthetics and criticism, and Latin American and US Latina studies, all of which is framed within Performance Studies.

On 14 October 2022, Vázquez visited the Museo Reina Sofía to take part in a series of master lectures in the Juan Antonio Ramírez Chair. This annual event of reflection around the historiography of art. In her lecture, To Hear What We See, she put forward a defence of music as a key component in any artistic project. Moving beyond its customary enjoyment, Vázquez points to music’s potential to activate and broaden aesthetic perception, in addition to being a vital resource for education.

This podcast spotlights the content of the lecture and includes a conversation around Vázquez’s two books published to date. The first, Listening in Detail: Performances of Cuban Music (Duke University Press, 2013), is an approach to Cuban music which evades nostalgia and encyclopaedic ambition; an attempt at new forms of listening and writing on her subject of study, and based on biography and detail. The second, The Florida Room (Duke University Press, 2022), is an invitation to become acquainted with Miami, the place from which, through music practices, some of the communities to have contributed to its history have grown: from Florida natives to migrants from southern Georgia and, of course, the Caribbean. All these communities find a place in the space which lends the book its name, an architectural device from which to render an account of the histories of memory, dispossession and survival which have habitually been reduced to obscurity and “mere” details.

Anquette, Ghetto Style, 1987

Alexandra T. Vázquez

Son 14, A Bayamo En Coche, 1979

Same Cooke, Live at the Harlem Square Club, 1963, 1985

Desmond Child And Rouge, Desmond Child And Rouge, 1979

Share

- Date:

- 30/05/2023

- Production:

- Rubén Coll

- Voice-over:

- Maria Mallol

- License:

- Produce © Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (con contenidos musicales licenciados por SGAE)

Audio quotes

- Dafnis Prieto Si o Si Quartet. Thoughts, Dafnison Music (2009)

- Dj Fingerz & Cutmaster Knobz. Miami, that bass so strong, Pandisc (1991)

- Son 14. Vamos, háblame ahora, Movieplay (1979/1981)

- Theodor Adorno / Moscow Symphony Orchestra. Op. 4: No. 6. Sehr langsam, TYXArt (2013)

- Machito and his Afrocubans (con Graciela Pérez). Mi Cerebro, Tumbao Cuban Classics (Circa 1945-1947/1997)

- Sam Cooke. Feel it, RCA (1963/1985)

- Anquette. Shake It (Do the 61st), Lil’ Joe Records (1987/2000)