NSK. From Kapital to Capital

Neue Slowenische Kunst. An event of the final decade of Yugoslavia

Transcription

NSK. From Kapital to Capital. Neue Slowenische Kunst. An event of the final decade of Yugoslavia

1. Laibach. An Alternative Slovenian Culture.

-Audio: Laibach. The Great Seal, Mute (1987)

On 4 May, 1980, Josep Broz, better known as “Tito”, died. Since 1953 he had been the President of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which constituted the republics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia.

-Audio: Laibach. Industrial ambients, Sub Rosa (1980-1982/2003)

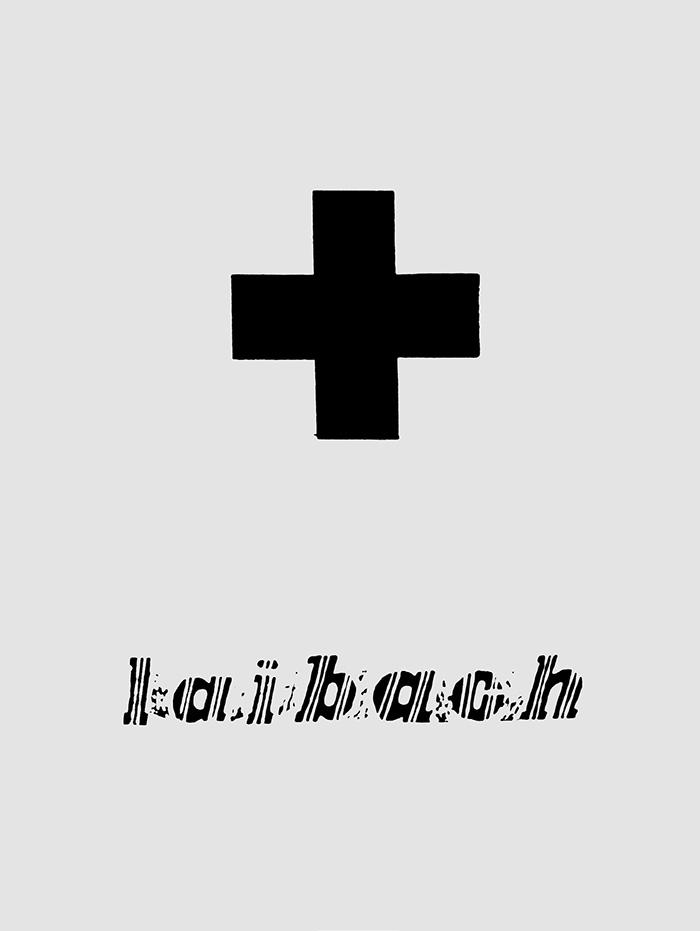

A few months after Tito's death, on 26 September 1980, Trbovlje, a small industrial city in Slovenia, awoke to its streets covered in posters to announce Alternativa slovenski kulturi (Alternative Slovenian Culture), an evening that promised an exhibition, a film screening, and several concerts by local bands. One of those bands, Laibach, would also put up additional posters: on some, their name appeared next to a drawing of a stabbing; on others, the name of Laibach appeared beneath a cross, resembling the suprematist cross by Kazimir Malevich whilst also bringing a totalitarian symbol to mind.

The authorities, who considered these posters to be an attack against Socialist ideology, would cancel the event, despite its backing from the ŠKUC, the Student Cultural Center of Ljubljana, in the Slovenian capital.

Yugoslavia was an exception within the framework of Eastern Europe, due to its status as a neutral country that afforded it independence from the two dominating superpowers during the Cold War. Regardless, without Tito its future was plagued with doubt. On an economic level, Yugoslavia was plunged into debt and, as a result, by 1983 it would have to comply with the guidelines set forth by the International Monetary Fund. On a political level, Tito's death meant "the loss of the symbolic point of reference” that united the different republics of the Yugoslavian state (see: Tomaž Mastnak. "The 1980s: A Retro Future", in Zdenka Badovinac, Eda Čufer and Anthony Gardner (eds.). NSK. From Kapital to Capital. MIT Press, 2015, pp. 538–539). With the aim of maintaining stability, repression tightened its grip, causing social movements to organise for democratic reforms and nationalist movements to gain in strength.

In this context, one of the ways in which youth discontent became palpable was through the punk movement, which developed in Yugoslavia almost in parallel to the United Kingdom. This phenomenon, which may seem surprising coming out of a Socialist State, was due to Yugoslavia’s relative opening out to the rest of the world.

In Slovenia, among the first bands to emerge from this subculture were O!Kult, Otroci Socializma, and Pankrti, whose song Lublana je bulana (Ljubljana Is Sick), from 1978, revealed that generational unrest was already present before the death of Tito.

-Audio: Pankrti. Lublana je bulana, Rest in Punk (1978/2016)

Pankrti, as well as the other bands mentioned, were linked to the ŠKUC, a cultural centre that in addition to hosting exhibitions, conferences, and concerts, also served as a publishing house. In fact, Pankrti would release their first single through that centre and would make their live debut at the opening of an exhibition dedicated to a group of conceptual artists called OHO. The ŠKUC, along with the radio station Radio Student, the magazine Mladina, and the FV Club, also known as Disco FV, made up the principal channels of communication of the alternative Slovenian scene, which also included Laibach and the future NSK. Therefore, we will consider the testimony of Dušan Mandič, a member of IRWIN — one of the founding groups of NSK — who in the early 1980s served as director of the ŠKUC:

Dušan Mandič: When the ŠKUC gallery opened there was the possibility to present some alternative art scene, so we started to represent other movements, not only painting like before, presenting different kind of practices in art like performance, video-art... And then we invited artists from different cities of Yugoslavia, it must be noted that Yugoslavia at that time its main city was Belgrade. So we invited people like Goran Đorđević from Belgrade, Mladen Stilinović from Zagreb. So through these presentations of these artists from other places we represented different kinds of art involvement. But at the same time in ŠKUC in Ljubljana, it was very strong, at the end of the seventies, the alternative scene and the punk movement. As you mentioned before, the group Pankrti started in 1977, 1978, and they got their first concerts in ŠKUC. And in relation to this punk scene very important place was FV Discotheque, which was a self-invention of a few people... This discotheque thing involved not only pleasure but they involved art production like different photograph expositions, then concerts, then video production, then all the punk bands they played there, they were filming videos or rehearsing. All these things were going through the three places of the discotheque that was at that time in Ljubljana. Because of the big social pressure and the police it was closed first one and then it moved to another place and at the end of 1984 to a third place, so there was like a big pressure on the space. And at the same time through the gallery we had a big production of audio tapes of all the groups, we produced the first LPs of the punk bands, later on of Laibach [Interview conducted by Rubén Coll in Madrid on 26 June 2017 ].

As noted by Mandič, the alternative scene would come under pressure from the authorities, who saw it as a type of threat. But if anything characterised that scene it wasn't so much the desire to replace the Socialist system, but rather the search for alternatives from within. Thus, instead of consigning their practices to the underground, its members decided to begin constructing their own institutions (see: Marina Gržinić. "Total Recall. Total Closure", in IRWIN (ed.). East Art Map. MIT Press, 2006, p. 323).

In Laibach's case, what differentiated them from their partners in punk was that, beyond simple provocation, the group from Trbovlje were set on exploring the relations between culture and ideology through art (see: Laibach. "10 Items of the Covenant", in Zdenka Badovinac, Eda Čufer and Anthony Gardner (eds.). NSK. From Kapital to Capital. MIT Press, 2015, p. 460). They would also use a maxim — not free from controversy — as their starting point, namely: “Art and totalitarianism are not mutually exclusive.” (Laibach. "Art and Totalitarianism" in Ibid., p. 464). Dejan Kršić claimed that this phrase was, in fact, a reversal of a quote by Vera Horvat-Pintarić, a writer who maintained that freedom was the essence of artistic creation — inconceivable within a totalitarian system (see: Dejan Kršić. "Fragments on the Matter of New Collectivism", in Ibid., p. 389). It was an assertion that negated the classification of art to cultural production promoted, for example, by Nazi Germany or those countries in which Socialist realism constituted the sole aesthetic option. For Horvat-Pintarić, these models opposed the tradition of Modernist art; despite her good intentions, this position was not free from risk, since denying the capacity to produce art in totalitarianism was a way of rejecting those regimes without making the effort to comprehend them, a task that becomes indispensable in being able to overcome them. Similarly, it presupposed that where Modernism had developed, one lived in freedom.

For this reason, Laibach decided to employ an identification with ideology in their modus operandi (Laibach. "10 Items of the Covenant", in Ibid., p. 460), in part because ideology depends on how reality is presented to us. In this way, Laibach proceeded to reveal the most irrational ideological aspects, addressing what is often censored or negated, but not resolved, with the aim of avoiding their subsequent return.

-Audio: Laibach. Država (Studio Version), Mute (1982/1993)

In Laibach’s track Država (The State), the last phrase uttered translates from Slovenian as “with us, power is held by the people”, which could synthesise the aspirations of self-managed Socialism, the official ideology of Tito's Yugoslavia.

In theory, with self-managed Socialism power was in the hands of the people. To give an example, the decisions of a workers' board on the subject of industrial production could be considered sovereign, yet on a political level it depended on the decrees of the Yugoslav League of Communists, the only existing party in a country where, paradoxically, there were supposedly no political parties. The League had an enormous number of delegates who acted as “representatives” of the working class (see: Todor Kuljić in Branislav Jakovljevic. Alienation Effects. Performance and Self-Management in Yugoslavia. 1945-91. University of Michigan Press, 2016, p. 5). A similar concept of self-management would, of course, be questioned by the alternative scene, which began to articulate its criticism via the contributions of the Ljubljana School of Psychoanalysis, the members of which included Mladen Dolar, Slavoj Žižek, and Rastko Močnik.

In self-managed Socialism, domination depended on the ability of bureaucrats to present themselves as representatives of the working class, yet simply demonizing bureaucracy would not solve the problem for, as authors such as Lacan and Althusser have noted, domination was not possible without the active collaboration of the dominated (see: Rastko Močnik. "How we were fighting for the victory of reason and what happened when we made it", in NSK Embassy Moscow. How the East Sees the East. Obalne Galerije Piran, 2015, pp. 84-85). This idea is key to understanding the work of Laibach, and one with which they would come face to face as they turned into a communication guerrilla in all its different manifestations: flyers, fanzines, communiqués, manifestos, not to mention interventions in media and institutions, and of course with music, their medium of choice: "(...) because of its status as the most ubiquitous contemporary form (...)" (Alexei Monroe. Interrogation Machine. Laibach and NSK. MIT Press, 2005, p. 38).

-Audio: Laibach. Cari amici soldati - Jaruzelsky, Mute (1982/1993)

In the early days, Laibach's performances were a highly intense experience, where elements converged that were hard to imagine at a conventional rock concert: an abrasive sound; a stage with rituals more often associated with a political rally; musicians that were blasé towards an audience who might have been caught off guard by smoke bombs being thrown. But beyond the uniforms, the “staged” violence, and the rhetoric and symbols worthy of suspicion, Laibach had no indoctrination intentions. In fact, as Alexei Monroe remarked, their performances ought to be viewed as “a call not to action but to (enforced) reflection.” (Ibid., p. 58).

If totalitarianism was characterised by a demand for a single possible reading of its cultural artefacts, then Laibach thwarted this type of reception through disconcerting eclecticism. On stage, just as on their flyers or on their albums, contradictory symbols were juxtaposed, thereby evoking the early avant-garde as much as the opposite: the Third Reich and Stalinism, in addition to national iconography. Their consciously incoherent stage presence perfectly summed up one of their earliest manifestos: “All art is subject to political manipulation, except for that which speaks the language of this same manipulation” (Laibach. "Art and Totalitarianism" in Zdenka Badovinac, Eda Čufer and Anthony Gardner (eds.). Op. cit., 2015, p. 464).

Although we previously touched on Laibach's modus operandi comprising the identification of ideology, perhaps it would be better to speak of “over-identification,” a concept introduced by Slavoj Žižek to understand the unique strategy with which Laibach, or even NSK, hoped to weaken the ideology they were confronting. For instance, Mladen Dolar expounded that “one over-identifies at the point where one doesn’t want to identify” (Mladen Dolar. "State of the Art", in Ibid., p. 448). Consequently, Žižek explains in more detail his understanding of over-identification in the case of Laibach:

Slavoj Žižek: They were deeply misunderstood, the usual perception by liberals who supported them was "they imitate, make fun of totalitarian fascist rituals" and then liberals always were "but what if young people will take them too seriously that they will not see the joke, that it's just a parody". No, it was not a parody, it's crucial that they genuinely enjoyed it, but in a way that a true fascist would never have enjoyed it. This is over-identification. You know who did the same? Did you see Chaplin's Great Dictator? What he does when Hitler gives speeches... You don't understand words, just some strange sounds and you understand every five minutes very vulgar words...

In this sense imagine Hitler doing a speech but imagine him over-identifying with it, so obviously enjoying his gestures that he just imitated them and all become meaningless. I think that to do this is much more subversive than just rationally criticise Hitler. You copy him more faithfully than himself and then in this way you make him ridiculous but, at the same time, it's very serious. Laibach are not good liberals who just imitate and criticise totalitarianism, they confront us with a very unpleasant fact that we, in a perverse way, deeply enjoy identifying with totalitarian rituals.

Much more important than to just criticise totalitarian rituals is to undermine them from within, to undermine their satisfaction. This is what I call over-identification. Imagine Hitler speaking and then going on into pure nonsense... just making sounds. Once I used another example, imagine watching an opera on television and then in the middle of the acting aria the sound disappears and how stupid are all of the gestures of the actors... Something like this... because the problem with totalitarianism is to break the spell of these rituals, we can do this rational analysis of manipulation, mass psychology... but the problem is to break the spell from within and that's what I think in a very ambiguous way Laibach were doing [Interview conducted by Rubén Coll in Madrid on 30 June 2017].

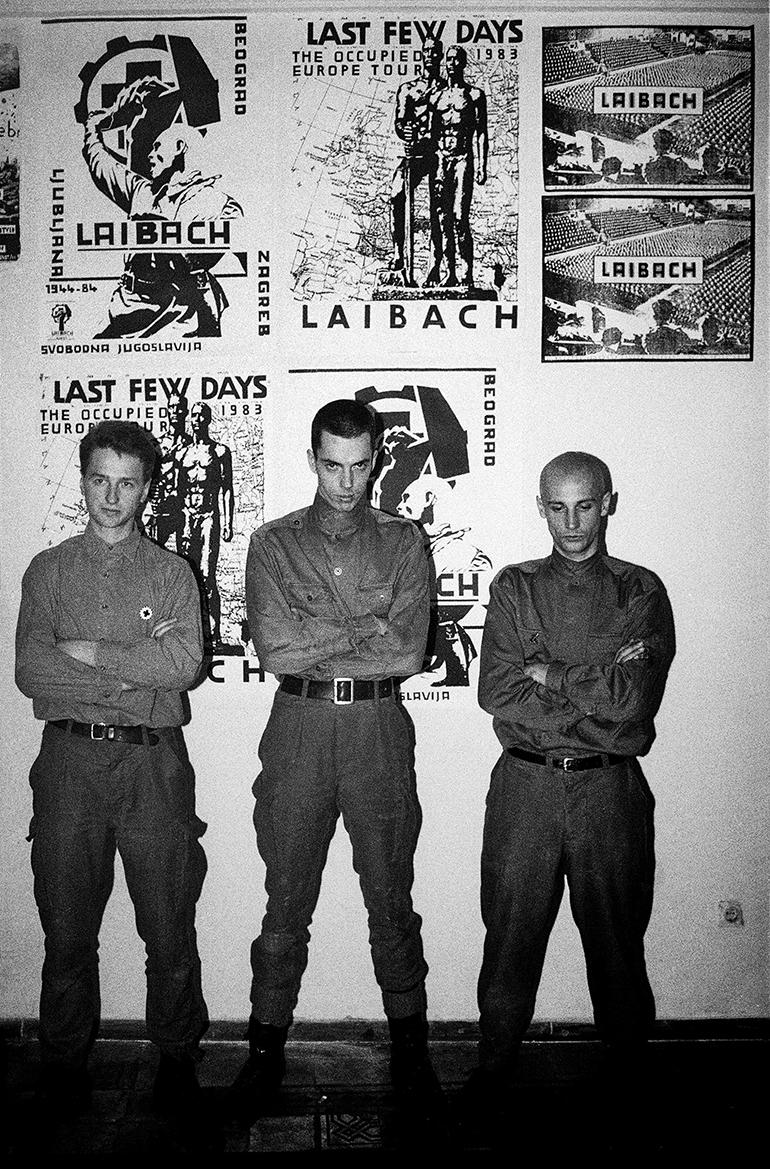

On 23 June 1983, Laibach were invited on a television programme which actually sought to subject them to a type of media lynching for their links to the alternative scene. The group cleverly took advantage, turning what was going to be an interview into a performance. However, the majority of viewers wanted to see confirmation through their television appearance that the alternative movement, and especially the punk movement, had ties to the extreme right.

The outcome of their appearance wouldn't take long to rear its head and the City Commission of the Ljubljana Socialist Workers' Labour Union took the stance that the group could not participate in public events, nor could they use the name Laibach, arguing that it was inappropriate, lacked legal grounds, and was against local ordinance (see: Jana Intihar Ferjan. "Chronology of Neue Slowenische Kunst and its Groups 1980–1992", in Ibid., pp. 508–509). The ban would stand until 1987.

What could have been seen as a setback that was hard to accept, turned out to be a small victory — the act of censorship had allowed an unresolved conflict to be put on the table. If Laibach was a word that caused indignation it was because it had been the name of Ljubljana, the capital of the Republic, at different points in its history, and all under German rule. It was a situation that had existed since the 12th century, when Christians of Germanic origin conquered the Pagan Slavs, but also in more recent times, when it was ruled by the Austro-Hungarian monarchy until 1918; and also, beginning in 1941, when Nazi Germany occupied Slovenia, making way for a brief period of collaborationism (see: Alexei Monroe. Op cit., p. 155).

Ultimately, it was a history of attempts at cultural assimilation that made the revival of the Laibach name an intolerable insult, not only for the partisans that had fought against Nazism, and for whom Laibach felt sincere respect, but particularly for the proponents of an ideology that had gone unnoticed until the death of Tito: nationalism. Laibach would confront those supporters with what all nationalist historiography preferred to silence: the fact that the culture and identity that they called for were structured around a “spectral history of (…) repressed paradoxes and wounds.” (Ibid., p. 17).

-Audio: Laibach. Vojna Poema (War Poem), Cherry Red (1986)

2. Retro-principle, Retro-avant-garde, and Retrogarde.

-Audio: Laibach. Sredi Bojev (In The Midst Of Struggles), Mute (1984/1997)

At the end of 1984, practically a year on from the time Laibach were banned from using their name or appearing in public events, its members decided to join forces with two other local groups: IRWIN and the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre (SNST), the former working in the visual arts, the latter in dramatic arts. The NSK (Neue Slowenische Kunst, German for New Slovenian Art) collective would emerge out of the confluence of all three.

The foundation of NSK brought with it the creation of a fourth, design-based group, New Collectivism, which included members from all three founding groups. Later, new sections would be created, making way for a highly complex organigramme sharing certain similarities with a State institutional structure.

NSK was born out of a hankering to renew national Slovenian art due to an impression that it was almost non-existent beyond their borders. Therefore, they sought to position it at the crossroads that Slovenia occupied between East and West, but stressing how predominant Western culture had defined their place on the international scene.

According to Dragan Živadinov, the founder of the SNST, NSK drew inspiration for choosing their name from the Expressionist magazine Der Sturm, which, in 1929, dedicated a special issue to Young Slovenian Art (Junge Slovenische Kunst) (Interview conducted by the author in Madrid on 27 June 2017). At the same time, another source of inspiration for the collective was the Liberation Front that helped Slovenia to unite anti-Fascist forces during the Second World War.

Next, two members of IRWIN, Andrej Savski and Miran Mohar, the latter also a member of the SNST and New Collectivism, talk about aspects related to founding NSK.

Andrej Savski: The groups were existing... Laibach from the eighties, IRWIN from 1983 and the Scipion Nasice Sister Theatre also in 1983, but we had this common thing that was this relationship towards the retro-principle and towards collectivism. Some of the people knew each other from the school from before and we had in the history of Slovenia, in fact, from war history, the Second World War, there was this association of different parties coming together to form the Liberation Front. In that sense, when we had this meeting of establishment of the NSK, we were basically trying to amass together different energies, and to amass also the power of be able to position ourselves in another — situation of the socialist government.

Miran Mohar: We were living in the context of socialism. If you compare the system in Yugoslavia and Russia, the Russian system was rather more totalitarian orientation and the Yugoslavian was more authoritarian. We came from this tradition and for us was important also this idea of egalitarianism which is the basic fundamental of socialism and communism, of course.

We were not critical to socialism or to communism, we were more on the position that we wanted to have more socialism and more authentic communism because what was the communism in the East and socialism it was a kind of a very much bureaucratic understanding of it. For some it was not communism, it was a kind of state capitalism.

We were also coming from industrial cities around Ljubljana and we were trying also to collect the energies, as Andrej said, the knowledge, and also to replace the lack of the art system. This idea of coming together was to concentrate knowledge and economy as well, both. But it's important to mention that each of the groups — IRWIN, Laibach, the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre — was completely independent, conceptually and financially [Interview conducted by Rubén Coll in Madrid on 26 June 2017].

The different NSK groups, in addition to sharing an interest in the workings of ideological mechanisms, were suspicious of individualism and the concept of originality, leading them to adopt a particular system of citations that could perhaps be called appropriationist and which they would classify under the term “retro”. Each NSK group would take on a different name: Retro-avant-garde, in the case of Laibach; Retrogarde, in the case of the SNST; and Retro-principle, in the case of IRWIN and New Collectivism.

Andrej Savski was, along with Roman Uranjek, one of the first to formulate this work method; hence it is pertinent to retrieve an excerpt of an interview in which Savski explains the reasons behind IRWIN and other NSK groups adopting the retro-principle.

Andrej Savski: The practice that we as a collective decided had to be in a certain way rational. What we decided was the retro-principle and we came to the point that we wanted to do is not to make a style but something like a thinking principle. So the principle would be working on the elements of the history of art as sentences, as signs, to put together elements that would be of different motifs and works but that would bring together a new sentence. That meant a lot of different approaches to works, from the articulation of the language to the discourse and one of the elements that was key was basically what we called the "dictate of the motif"; the motif itself would already tell us, if you were looking from different perspectives, from the positive and negative aspects, what we would already decide… which methods were going to be used in presenting it. Basically we were all indebted to Duchamp and his method of objet trouvé and that can be seen throughout the works both the theatre group, the design group and the music group [Interview conducted by Rubén Coll in Madrid on 26 June 2017].

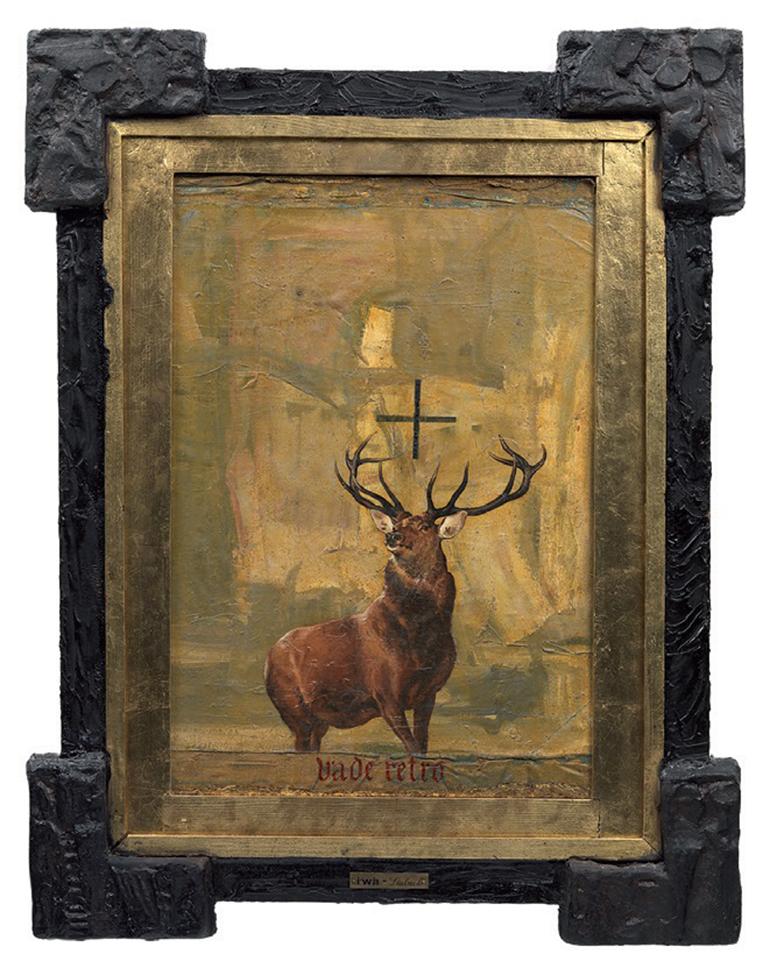

One of the most important expressions of putting the retro-principle into practice would be the project of IRWIN Was ist Kunst, “What is Art?” in German, which was, first and foremost, a reflection on how a national idea is constructed in painting. For this reason IRWIN would focus their work on creating compositions based on motifs originating from the history of Slovenian art. Upon beginning the project in 1984, coinciding with the censorship of Laibach, the members of IRWIN would decide to integrate the symbols that Laibach had been using for their group’s image into their paintings, as if it were just another symbol in Slovenian history: the silhouette of a sower, a stag or, for example, the equilateral cross which Laibach would use to replace their name in the period when they were prohibited from using it.

As one can imagine, the paintings of IRWIN showcased an eclecticism similar to that already present in Laibach, with a gaze that always rested on times from the past. According to Boris Groys, it was a way of uniting forces that had broken and modernised national identity (see: Boris Groys."NSK: Del socialismo híbrido al Estado universal" en Zdenka Badovinac, Eda Čufer y Anthony Gardner (eds.). NSK. Del Kapital al Capital. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2017, p. 167) This was aligned with, according to IRWIN and Eda Čufer, a member of the SNST, the chief premise of NSK’s retro-avant-garde was that “the traumas from the past affecting the present and the future can be healed only by returning to the initial conflicts.” (IRWIN., Eda Čufer. "NSK State in Time", in Zdenka Badovinac, Eda Čufer and Anthony Gardner (eds.). NSK. From Kapital to Capital. MIT Press, 2015, p. 501).

-Audio: Laibach. Bogomila - Verführung, Sub Rosa (1986/1988)

As the 1980s moved on, the alternative scene, and by extension NSK and its groups, stopped being seen as a threat and began to be considered as one more player in the new social movements demanding institutional modernisation. This acceptance was achieved thanks to organisations like the League of Socialist Youth of Slovenia, which awarded the NSK the Golden Bird Prize in 1986, given to the best cultural workers.

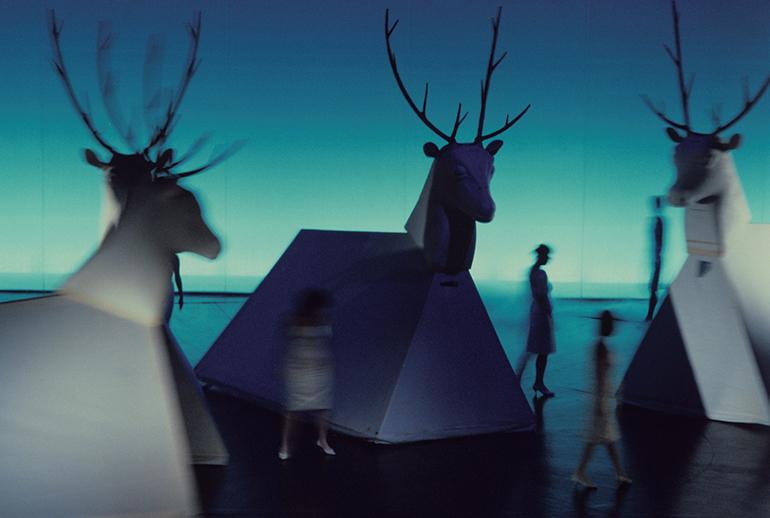

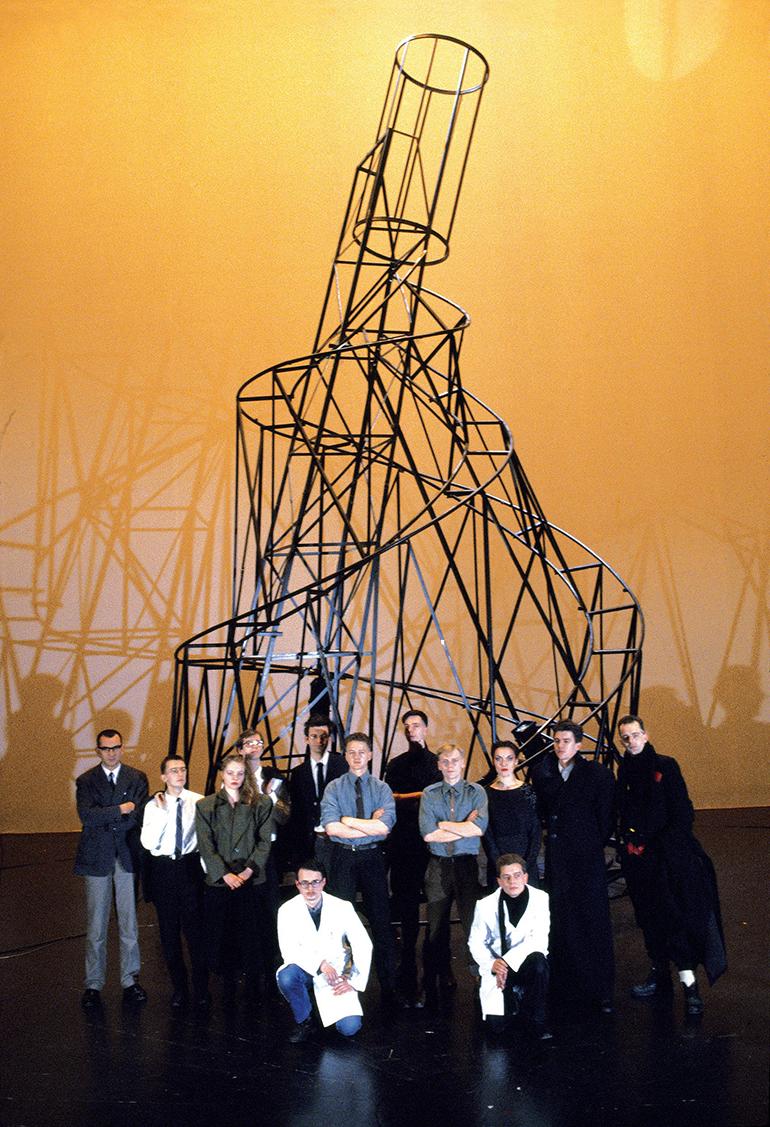

The reason for the prize was the "accomplishment of artistic synthesis, the result of the cooperation and mutual influence (...)" (Jana Intihar Ferjan. "Chronology of Neue Slowenische Kunst and its Groups 1980–1992", in Ibid., p. 516) among the principal NSK groups, who had brought to fruition a project conceived and directed by the SNST: the Retrogarde Event Baptism under Triglav, a gesamkunstwerk in which “Laibach provided the music, New Collectivism designed the visual identity of the project and took charge of public relations, and IRWIN collaborated in producing the monumental set design”. (Eda Čufer. "SNST, Retro-Classical Stage, Retrogarde Event Baptism under Triglav, Cankarjev dom, Ljubljana, 6 February 1986" in NSK. From Kapital to Capital. Exhibition Guide. Moderna Galerija, 2015, p. 20)

The SNST was a platform which, since its foundation in 1983, equated the theatre with the State. In conjunction with Slovenian Culture Day, this NSK group were invited to the Cankarjev Dom auditorium to perform the most important work by the leading authority in Slovenian literature: France Prešeren. It entailed taking the epic poem Baptism on the Savica to the stage, the storyline of which “concerns, or rather, it is constitutive of (...) [the Slovenian] national identity” (Eda Čufer. “Athletics of the Eye: Baptism and the Problem of Writing and Reading Contemporary Performance", in Zdenka Badovinac, Eda Čufer and Anthony Gardner (eds.). Op. cit., 2015, p. 238).

However, as Katja Praznik noted, the SNST preferred to replace nationalistic logic with that of transnationalism (see: Katja Praznik."Ideological Subversion vs. Cultural Policy of Late Socialism. The Case of the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre", in Zdenka Badovinac, Eda Čufer and Anthony Gardner (eds.). Op. cit., 2015, p. 358) by applying two changes or shifts:

-Audio: Laibach. Črtomir, Sub Rosa (1986/1988)

Firstly, the story now took place within the framework of 20th century revolutionary culture, instead of going back to the mythical pagan age when Slovenians lost their national autonomy to Germanic Christianisation. Secondly, literature was displaced as the preferred medium when contributing to national construction, with avant-garde art chosen to construct an international revolutionary culture (see: Eda Čufer. Op. cit., 2015, p. 20). This particular application of retro-method replaced Prešeren's dramatic text with 62 iconic works like Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, which became a backdrop for actors and dancers sharing a space with national Slovenian symbols and NSK symbols (see: Branislav Jakovljevic. Op. cit., p. 271).

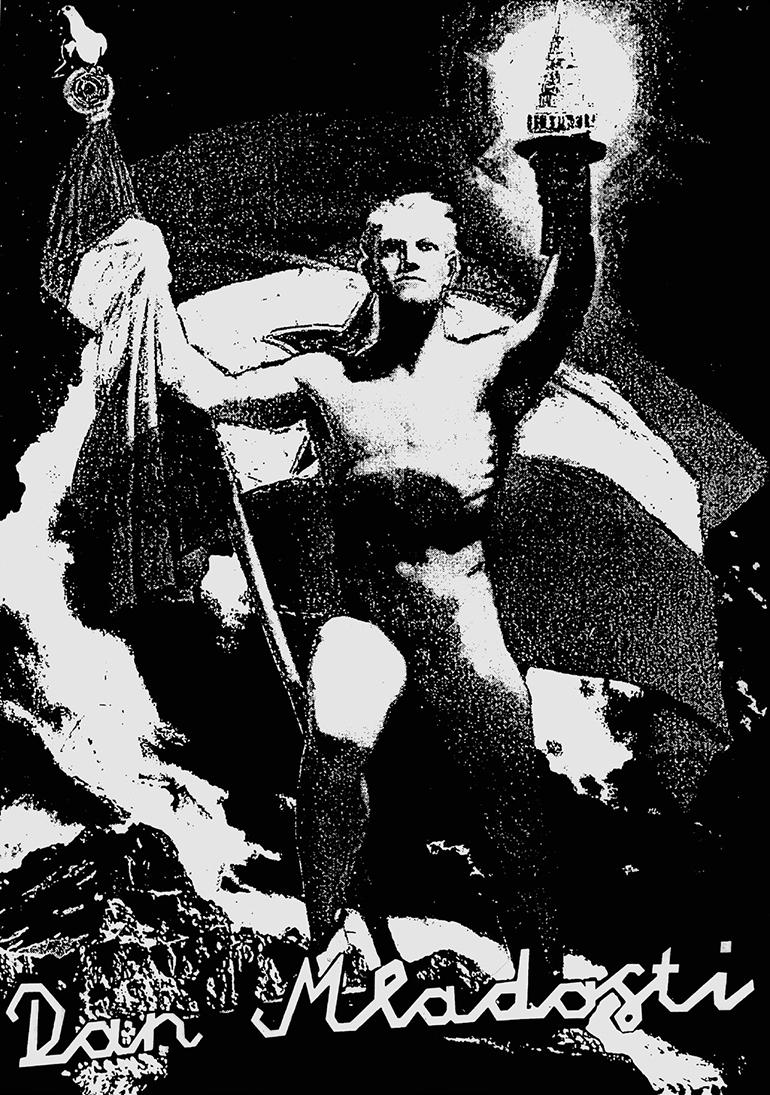

The Retrogarde Event Baptism under Triglav was a hit and the SNST would receive another invitation from the League of Socialist Youth of Slovenia, this time to contribute to another key event on a State level: Youth Day, which every 25 May commemorated the thousands of youths killed in the Second World War defending the future Socialist Yugoslavia. Yet the theatre group would never get to carry out the project they had envisioned due to the scandal ensnaring New Collectivism, who were also invited to design a poster for the occasion.

Youth Day revolved around a type of ritual, which involved, every year, a relay race in which youths from all over Yugoslavia carried a baton which must finally be passed to Tito as a symbol of brotherhood and unity between the different republics.

The problem was that in 1987 there was a high level of scepticism surrounding the ceremony, especially in Slovenia — Tito had been dead for seven years, so it seemed strange to continue to pay tribute to him. At this juncture, New Collectivism decided to base their Youth Day poster on a propaganda image by Richard Klein: The Third Reich: Allegory of Heroism. Yet the only thing that remained from it was the Aryan youth who appeared in the foreground, with the rest of the accompanying symbols subtly replaced: the imperial eagle with a dove of peace; the swastika flag with a Yugoslavia flag; and the torch carried by the young man was turned into the dome of Slovenian parliament, designed, but never completed, by Jože Plečnik.

Miran Mohar: The jury liked the poster very much, otherwise they would not have chosen it, until the moment when an engineer from Belgrade, Nikola Grujić, published in the main Yugoslav newspaper the story where this poster was coming from. And after the story everything changed... The jury said: "We liked the poster but you didn't tell us it was a nazi one"... So it was this idea of the hidden message which was not visible. What we produced is only possible to understand basically from the context. Of course, with this action we had a critique about the cult of personality which is even more problematic on the left because on the right is standard. On the left, with all these egalitarian ideas it should be different. We were claiming for more participatory socialism and we didn't know what was going to happen and it was discovered.

Later on, it came out very interesting that the engineer Grujić, who sent his letter, he was an avatar of the Yugoslav secret police. This person doesn't exist, we never found him.

With the SNST I was also involved in the preparation of the scenario. It was also a kind of radical idea, a big celebration on the mountain lake Bohinj, on a beach which should be an artificial island, with a kind of constructivist version of a non-existing parliament drawn by the plans of Jože Plečnik. And from Triglav a helicopter would fly and land in the middle of the lake the same guy you could find on the poster and then there would be a kind of ballet, a contemporary dance. The public will come to the island with boats. And the idea was that we would like to repeat this theatre performance in London. The generals liked the idea but they didn't know the poster yet.

Then the media exploited, hundreds and hundreds of articles, radio broadcasting, TV reports on this issue about this gang of four who did the poster because they were not chasing the whole NSK but what was problematic was the poster itself. They said that we wanted to ruin Yugoslavia and ruin the image of the president Tito. To make this long story short, after these all procedures the story leaked out. It went beyond the Yugoslav borders and you would have articles in America, Austria, German, even in Japan... After maybe a year the general prosecutor, Slovenian, decided that we were using a legal artistic retro-principle or retro-avant-garde language which creates a multilevel meaning and basically accepted or recognised it as an art [Interview conducted by Rubén Coll in Madrid on 26 June 2017].

New Collectivism's image was never used, but at least the “Relay of the Absurd,” as the League of Socialist Youth of Slovenia called it, did not take place, demonstrating the impossibility of a generational replacement that could promise Yugoslavia a future without drastic changes.

3. A State in Time

Apart from the Youth Day scandal, 1987 was the year in which the so-called Slovenian Spring began, which would make way for the establishment of democracy and independence.

A certain unanimity exists in asserting that the beginning of this period coincides with the Nova Revija magazine putting out a monograph entitled Contributions to the Slovenian National Program. In it, several intellectuals expressed the need to embrace a multi-party system and to restore Slovenia's sovereignty, transforming it into a country that did not have to depend on Yugoslavia (see: Rudolf Martin Rizman. Uncertain path. Democratic Transition and Consolidation in Slovenia. Texas A&M University Press, 2006, p. 161). In part, it had to do with a reaction to another document that appeared in a neighbouring republic: Memorandum of the Academy of Arts and Sciences of Serbia, a controversial text in which Serbian nationalists demanded a centralist rethinking of the State that would offset the unfair treatment to which the Serbs had supposedly been subject in Yugoslavia, despite being the biggest population. The text would be interpreted in Slovenia as an expansionist and hegemonic gesture (see: Alexei Monroe. Op. cit., p. 147).

In 1987 Laibach also released their first single, Geburt einer nation, Birth of a Nation in German. In truth, it was a peculiar re-interpretation of the song One Vision by the British group Queen and meant Laibach were entering uncharted territory, pop for the masses, bringing the band greater recognition among Western audiences. Beyond trying to conquer other markets, this stylistic change was meant to highlight the fact that the music industry in the West was capable of producing cultural goods with a certain totalitarian slant. But the song also could be considered a synthesis of the concerns of Laibach and NSK at the time: on one hand, the tensions derived from the desire for national affirmation within Yugoslavia; on the other, the perception of an imminent threat in the form of cultural Westernisation. It is no coincidence that the United States National Anthem is the first thing that is heard as a type of prologue to the track.

-Audio: Laibach. Geburt einer nation, Mute (1987)

Geburt einer nation appeared on the album Opus Dei, the first by Laibach to be officially released in Yugoslavia, with the group preparing a communiqué for the release in which they declared themselves in favour of internationalism, advocating the destruction of boundaries because, in their own words, they knew "what they are made of and how they are built” (Laibach. "Address at the occasion of Opus Dei Album Release in Yugoslavia", in Neue Slowenische Kunst. Amok, 1991, p. 67).

-Audio: Laibach. Across the universe, Mute (1988)

During the Christmas of 1988, Laibach again applied their retro-principle to pop music, this time to the Beatles, whose Across the Universe contained a perfect lyric to reflect the general belief that the future of Yugoslavia was via Socialism, albeit in a democratised version, an idea that was confirmed as implausible by 1990. First, with the petition of the League of Socialist Youth of Yugoslavia to specifically eliminate the word “socialist” from the name of the Slovenian State, and shortly thereafter with the first elections held in April of that year, won by the Democratic Opposition of Slovenia, for whom democracy and socialism were completely incompatible. This clashed with the alternative scene, whose objectives never included the “deconstruction of the State as a public authority” (Tomaž Mastnak in Zdenka Badovinac, Eda Čufer and Anthony Gardner (eds.). Op. cit., 2015, p. 538).

By way of referendum, Slovenia would declare independence on 25 June, 1991, a decision that would be answered with an offensive by the Yugoslavian army, setting off the so-called Ten-Day War, a brief conflict that was the first in a series of clashes between different republics of a Yugoslav federation which had already started on an irreversible decline.

To avoid its integration into the new political order, NSK took it upon themselves to create their own State in 1992, unusually placing it outside of space and circumscribing it strictly in time. It was a decision that for Alexei Monroe meant “(…) to re-establish the State as a universal post-national category, a utopian framework that can transcend the conflicts caused by the desire for ethnically driven border demarcations” (Alexei Monroe. Op. cit., p. 253). To obtain citizenship and a passport from this State, one must simply apply for it.

The origin of this new State would come a few months after the dissolution of the Soviet Union was made official, and would take place in a Moscow apartment turned into an NSK Embassy, a project driven forward by IRWIN that would be carried out throughout May of 1992, almost at the same time as the beginning of the siege in Sarajevo by the Yugoslavian army, a bloody episode that would last until 1996, taking thousands of lives in the process.

Next, Mohar, a member of IRWIN, present at the NSK Embassy in Moscow, recalls the project:

Miran Mohar: This Moscow experience was very important. We opened the embassy and it worked, people came and this experience was tremendously important, we started to understand that the State could be an important channel of communication when there was a big fight for the land in Yugoslavia and Russia. It was even also our statement against being in one place, it was a message to nationalists. We created our own State in time not in space and then we didn't know what was going to happen but clearly it is evident even if the Marxist position was "the State must die", we know now that maybe the only force or power which protects us from neoliberalism is a State.

Basically, we consider the State as an extremely important form and NSK State gives the space for the people, for their projections of "what a State could be" and what are identifications. For instance, when we opened a passport office in Taipei, Taiwan we were doing some interviews and one man said: "I took NSK citizenship and NSK passport because it gives me some space between choosing being Chinese or Taiwanese", it's a third space. For some people, this is space is extremely important. It is symbolic but it's also real because the State is also a symbolical thing and when people believe in symbolical power, it becomes real [Interview conducted by Rubén Coll in Madrid on 26 June 2017].

After weeks of debate between NSK members and other Russian figures who were sympathetic to the collective, the NSK Embassy project would conclude with the drafting of the Moscow Declaration. It was a document that reflected the concerns of all present about the recent transformations of their countries of origin, and, in particular, of the consequences of the ideological replacement resulting from the triumph of liberalism after decades of Marxist-inspired governments.

The Moscow Declaration was made up of two epigraphs, each divided into various points, of which we will read three as a form of coda to this account of a decade that was NSK’s first and, at the same time, the last of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia:

“A. The history, experience and time and space of Eastern countries of the 20th century cannot be forgotten, hidden, rejected or suppressed.

B. The former East does not exist anymore: the new Eastern structure can only be made by reflecting on the past which has to be integrated in a mature way in a changed present and future.

C. This concrete history, this experience and this time and space have created the structure for a specific subjectivity that we want to develop, form, and reform; a subjectivity that reflects the past and the future”.

("Moscow Declaration" in NSK Embassy Moscow. How the East Sees the East. Obalne Galerije Piran, 2015, p. 46)

-Audio: Laibach. NSK, Mute (2006)

Bibliography

- Zdenka Badovinac, Eda Čufer and Anthony Gardner (eds.). NSK. Del Kapital al Capital. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2017.

- Zdenka Badovinac, Eda Čufer and Anthony Gardner (eds.). NSK. From Kapital to Capital. MIT Press, 2015.

- IRWIN (ed.). East Art Map. MIT Press, 2006.

- Branislav Jakovljevic. Alienation effects. Performance and Self-Management in Yugoslavia. 1945-91. University of Michigan Press, 2016.

- Alexei Monroe. Interrogation Machine. Laibach and NSK. MIT Press, 2005.

- Neue Slowenische Kunst. Amok, 1991.

- NSK Embassy Moscow. How the East Sees the East. Obalne Galerije Piran, 2015.

- NSK. From Kapital to Capital. Exhibition Guide. Moderna Galerija, 2015.

This three-podcast series pivots around Neue Slowenische Kunst (New Slovenian Art), organised in conjunction with the exhibition on this “collective of collectives” staged in the Museo Reina Sofía from 28 June 2017 to 8 January 2018.

NSK surfaced in 1984 as a convergence of Laibach, IRWIN and the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre, three groups hailing from different artistic disciplines that decided to join forces in Ljubljana — the capital of Slovenia, at that time one of the six constituent republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia — and, ultimately, chroniclers of Yugoslavia’s final decade. This period began with the death, in 1980, of Josep Broz - Tito, head of State and the unifying connection of a country in the throes of progressive transformation. This process would see self-managed Socialism make way not only for the establishment of liberalism and democracy, but also for the outbreak of armed conflicts, intersected by the desire for national affirmation and matters of ethnicity.

To this backdrop NSK went from being a collective born out of a will to revamp Slovenian art by exploring the relationships between culture and ideology to a kind of “State within a State”. Consequently, these three podcasts set forth a journey that starts in the early 1980s with the origins of the group Laibach, and is framed in an alternative cultural scene in Slovenia, which looked not so much to replace the socialist system but to reform it, culminating, in turn, in the creation of the “NSK State in Time” in 1992.

Furthermore, via interviews, these audio pieces compile the testimonies of certain prominent figures from this time period: the members of IRWIN, Dušan Mandič, Andrej Savski and Miran Mohar, the last of which also belonged to the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre and the design group New Collectivism; and philosopher Slavoj Žižek, who carried out some of the most cogent analyses on the transformations that took place in old Yugoslavia and, more specifically, NSK’s strategy and aspirations, based on Laibach’s work.

Laibach, Black Cross, 1980

Laibach posing at the Document Occupied Europe Tour exhibition, ŠKUC Gallery, Ljubljana, 1984

IRWIN, Vade Retro, 1988

A group portrait of NSK members and guests in front of the model of Tatlin's Tower from the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre production Retrogarde Event Baptism under Triglav, 1986

A group portrait of NSK members and guests in front of the model of Tatlin's Tower from the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre production Retrogarde Event Baptism under Triglav, 1986

New Collectivism, Youth Day poster, 1987. League of Socialist Youth of Yugoslavia

NSK Embassy Plate, 1992

Share

- Date:

- 22/08/2017

- Production:

- Rubén Coll

- Acknowledgements:

Sara Buraya, Rafael García, Chema González, Beatriz Jordana, Dušan Mandič, Ana Mizerit, Miran Mohar, Andrej Savski, Dragan Živadinov and Slavoj Žižek.

- License:

- Creative Commons by-nc-sa 4.0

Additional Material

Audio quotes

- Laibach. The Great Seal, Mute (1987)

- Laibach. Industrial ambients, Sub Rosa (1980-1982/2003)

- Pankrti. Lublana je bulana, Rest in Punk (1978/2016)

- Laibach. Država (Studio Version), Mute (1982/1993)

- Laibach. Cari amici soldati - Jaruzelsky, Mute (1982/1993)

- Laibach. Vojna Poema (War poem), Cherry Red (1986)

- Laibach. Sredi Bojev (In The Midst Of Struggles), Mute (1984/1997)

- Laibach. Bogomila - Verführung, Sub Rosa (1986/1988)

- Laibach. Črtomir, Sub Rosa (1986/1988)

- Laibach. Geburt einer nation, Mute (1987)

- Laibach. Across the universe, Mute (1988)

- Laibach. NSK, Mute (2006)