Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

Raciality and social struggles in the United States

Transcription

My name is Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor and I am the author of From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation. I’m also an assistant professor of African American Studies at Princeton University in the United States.

If the question is how does fascism become part of everyday life, which means… I think that we have to start with the question of whether or not we are actually living under fascism, whether or not we have fascist leaders that are sympathetic with fascists. Is there a fascist movement among us? I think that those are different things. Speaking from a perspective in the United States, I don’t think you can define American society as fascist. I mean, I think, you know, I think about fascism as a completely close police state where it is impossible for the left to operate without any freedom at all. And that is not what exists in the United States. And it’s not to say that what is happening in that country can’t result in fascism. It’s not to say that Donald Trump and the Republican Party in particular represent a particular threat to people, but I do think that we are at a point where, you know, we have a violently right wing government, but we are still able to organize. I mean, the largest, some of the largest protests in the American history have occurred in the last two years. So I don’t think that that can happen under fascism, but I do think that the threat is quite real. I think the possibilities of full-blown fascism are quite real. And in terms of why did this happen, or how does this happen, I think part of it has to do with the failures of social democracy, that when center left parties… Which in the United States is also very complicated because there are only two political parties and they both operate on the right wing of the political spectrum, to variant degrees. Of course the Republican Party is a hard right party that is a party of white supremacy; it’s a party of bigotry, anti immigrant hatred. The Democratic Party certainly does not embody those ideas, but they defer to the republican right wing. So I think that with the failures really of the Obama administration to respond in such way to the people who voted for him in a meaningful way, that changed their lives, that actually made a substantial impact on society, the failure to do that created an opening for Donald Trump. I think that the failures of central left politics on the formal sense in the United States, the weakness of the left have created a political opening for someone like Donald Trump to come into.

I think probably the first time it was this issue of minorities or groups that are oppressed who, how do they operate within a larger movement where there may be a minority without sort of diluting their particular issues, but being a part of the collective. So this probably was first articulated in American politics, left wing politics, in the late 1960’s, and 1970’s, when black feminist formations began to develop. So black feminism developed in response to both the inability of white feminism organizations to integrate an analysis of racism into their general politics and into their activism so they didn’t… Not only could they not… They didn’t talk about race as a factor that black women had to deal with. They didn’t have any political program around fighting racism. So issues around sterilization, for example, that affected black and Puerto Rican and other brown women, in particular the mainstream white feminist movement did not really have any sort of activism around. So it was in response to white women in the feminism movement on the one hand, but it was also in reaction to Black Power organizations that were dominated by black men, who also didn’t have any particular analysis of how race affected the lives of black women. So the failure of the dominant social movements in black power, in feminism, to take up the issues of black women compelled the formation of black feminist organizations. Which is very important, because it wasn’t as if they were just organizing separately on their own, but they actually theorized and took time to understand and articulate why black women issues needed to be understood on their own terms, which was to say that racism in gender issues had an overlapping impact in the lives of black women. So understanding race alone or understanding gender alone could not explain the conditions the black women dealt with. So this was in the late 1960s and 1970s, and those issues were never fully resolved in ways that many of the issues that came up… And the radical insurgencies of the late 60s and 70s were not involved because they identified capitalism as part of the problem facing these people. So the lack of resolution around many of these questions is meant that the Black Lives Matter movement is taking them up again. And so those issues… It’s particularly important in American society cause is such a racially, and ethnically fractured society. So there are enormous tensions between black women who organize in the Black Lives Matter movement and the women’s movement, which is not led primarily by the white women, but it seems largely as a middle class movement.

So there are race and class tensions that exist within the movement, but I think, in general, in the American context it’s been very important to talk about what the solidarity mean, what are the politics of solidarity. Because you have a situation now where Trump is, literally, attacking black people. He’s attacking Mexicans and Central Americans on the southern border of the United States, and he’s attacking Muslims. The Supreme Court just affirmed Trump’s Muslim ban, which bans Muslims from eight different countries from entering the United States, or from people in the United States going to those countries. It’s disgusting. So it is the necessity for the different groups to understand the relationship between the different oppressions, how they overlap, how they are different, but that there’s a need for connections in order to build a mass movement, because individually black people are a small percentage of the United States, only 12% of the population; Latinos are 13% of the population; Muslims are even smaller. So as each individual group is hopeless the idea that one particular group can take on the Trump administration or the United States government. It’s only together that we stand any chance of having any success. But you can’t come together on the basis of why we should just come together and not to pay attention to the particular ways each group is oppressed and experiences that. But instead of using that as a point of division, we have to show how these things are related to each other, and that we all have an interest in fighting the oppression of other people just as they have an interest in fighting the oppression of us.

Now, so what is the state of the movements of the oppressed in the United States? It’s very disorganized; it’s very weak right now. There is no transgender women’s movement in the U.S. There is not an immigrant’s rights movement in the U.S., even in the midst of these horrible attacks on immigrants. There is Black Lives Matter, but Black Lives Matter has been very demobilized since the 2016 presidential election. So I think all of the elements for a social movement exist. People are horrified about what is happening in the United States, but we know this, not just in the U. S. but everywhere, that there’s a gap between consciousness and whether people are angry and horrified and want things changed, and then the actual ability to do something, or the willingness to do something, or probably, most typically, the confidence to do something about the situation. So saying that there is not a social movement doesn’t mean that people aren’t doing anything. People are doing lots of things. There are isolated protests against police brutality and police murder, which continues to happen. In the United States there is organizing in some protests that have been organized among immigrant’s rights organizations, just as there have been smaller protests among Muslim organizations in the U.S. The protests and organizing them as it’s happening it’s too small given the extent to the attacks that are happening, but it’s a beginning, and I don’t even think that they’ll be small for very long. I think that the potential for a mass movement in the United States is quite great, but I do think that we have to learn from the movements that have happened in recent years. So whether it’s Occupy or even the beginnings Black Lives Matter, which is to say our movements need more democracy. They need more accountability from people who are assumed to be leaders. Within the movement there need to be more spaces for democracy, meaning more assemblies, more discussions where the people who constitute a movement have a say in what the movement is, what its politics are, what its strategies are, what its tactics are. The people have an ability to assess and to say whether or not a tactic has been successful because right now the leadership is unaccountable. They talk to themselves, they have no relationship to the people they say they represent. They often work for NGOs. The influence of foundation money, the Ford Foundation and other big corporate foundations, is quite extensive. And this is not democracy. This is a way to dissuade people, to convince people not to be in movements, because it’s just like politics, you don’t have a voice, and you don’t have any influence over what is happening. So democracy and accountability are central to organizing the mass movement. It doesn’t mean that we’ll win. Movements don’t win just because they’re right or that they should. You have to organize, you have to have strategies and you have to learn from your mistakes to not make them again, but that begins with democracy and having a place for people, all people, to be able to have a say in what is happening.

Keeanga-Yamahtta Tayloris an activist and theorist on Black freedom struggles and a lecturer in the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University. Show lessShe has published articles on social movements, urban politics and racial inequality in the USA, and is the author of From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation (Haymarket Books, 2016), which brings historical perspective to the present and indicates future struggles for Black liberation. In 2017 she published a new collection of essays entitled How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective.

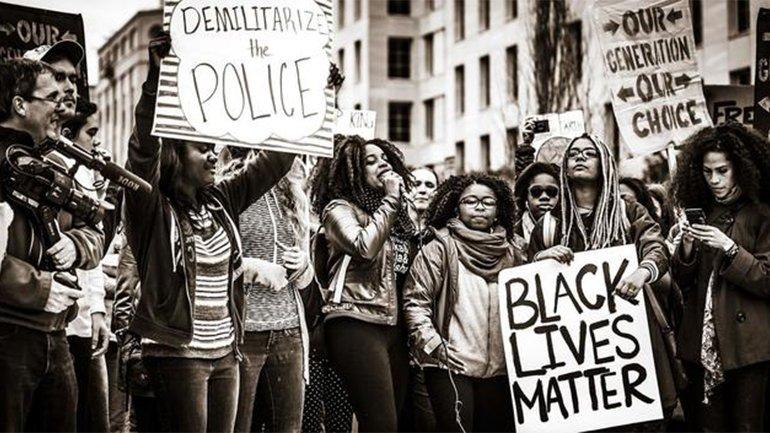

Protest of Black Lives Matter in Washington on November 10, 2015. Photograph: Johnny Silvercloud

Share

- Date:

- 18/02/2019

- Production:

- Elisa Fuenzalida & José Luis Espejo

- License:

- Creative Commons by-nc-sa 4.0